In 1984, Robert Rauschenberg was at the height of his fame.

“Rauschenberg was not a giant of American art. He was the giant of American art and, I would argue, the most important artist of the second half of the 20th century,” said Jade Dellinger of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Florida SouthWestern State College.

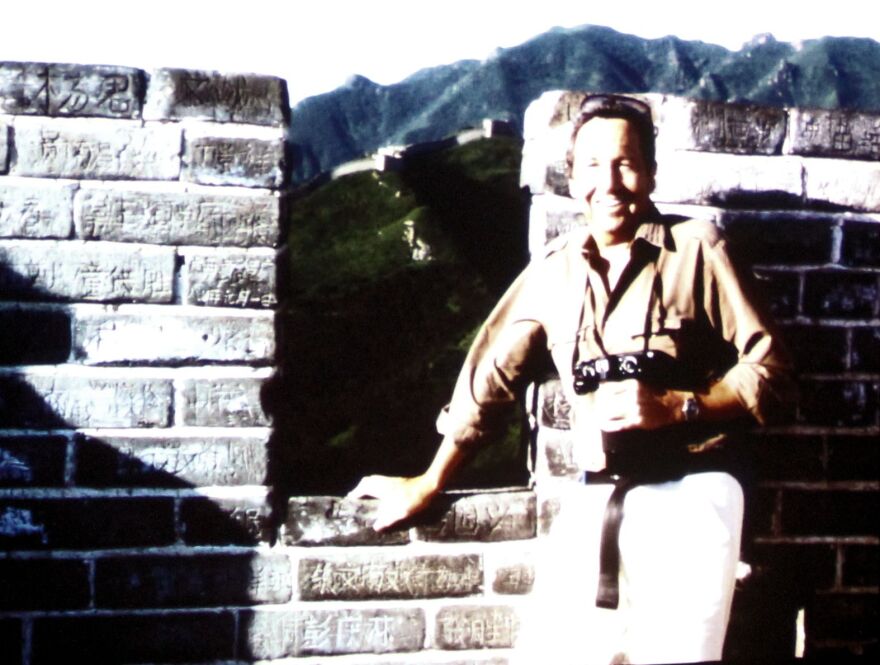

The artist decided to use his celebrity to take art to places where artistic expression had been suppressed. So in 1982, he made a trip to China to work with Xuan papermakers in Anhui Province.

That collaboration resulted in one of his most iconic artworks — a 100-foot-long print titled “Chinese Summerhall” and was the springboard for trips to a dozen other countries.

“Bob had always envisioned making a kind of peace mission traveling the world and going to places, frankly, where there were dictators and authoritarian regimes where it was difficult for Americans to travel to because he believed in one-on-one communication with people,” Dellinger added.

He named this initiative the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange, or ROCI. Between 1985 and 1990, he traveled to Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, the Soviet Union, Germany and Malaysia.

ROCI wouldn’t have happened without Donald Saff.

The former director of Graphicstudio at the University of South Florida made all the arrangements for these trips and oversaw the production of the multiples the artist created upon his return.

Rauschenberg had been introduced to Saff by friend and fellow artist Jim Rosenquist.

“Rosenquist came to Florida at the invitation of Graphicstudio around 1970,” Dellinger explained. “He had brought his … very young son and his wife, and they got in a car wreck in Tampa, and they ended up in the hospital for an extended period in ICU. Bob … came up from Captiva to visit.”

At the time, Rauschenberg was just beginning to experiment with printmaking. He had a small studio next to his beach house. It paled in comparison to Graphicstudio.

“Graphicstudio had all these printmaking facilities, and they would give him as expansive a studio environment as he cared to work within,” said Dellinger. “So, he started making prints in 1972 and then through the entirety of his life he made work really connecting with Don Saff and Graphicstudio.”

This strategic partnership culminated in some of the greatest artworks of the last half of the 20th century, including his “Made in Tampa” series of clay works, hundreds of lithographs and scores of solvent transfer prints.

This work helped cement Rauschenberg’s reputation as the pre-eminent global artist of his time and tethered him to Southwest Florida, where he had everything he needed to make great art and create a lasting legacy.

“One of the things that I think kept him in Florida was having this deep relationship with … the University of South Florida,” Dellinger said.

MORE INFORMATION:

Donald Saff established Graphicstudio at the University of South Florida in 1968.

“He sets it up as this print and multiples atelier to create lithographs and other prints by visiting contemporary artists,” Dellinger explained.

Rauschenberg’s cardboard boxes and ‘Made in Tampa’ series

Rauschenberg began making editioned prints at Graphicstudio beginning in 1972. At the time, he was still unpacking boxes at his beach house on Captiva. He decided to transform those boxes into art. Dellinger provided context.

“In New York, Rauschenberg would walk along the blocks around his home and studio and collect detritus which he’d then incorporate into his works of art,” said Dellinger. “He could no longer do that once he moved to Captiva. So, he decides to make use of the boxes that had moved his art and life to Florida.”

They were ratty looking, but that appealed to the artist.

“He liked that they'd been beaten up, that they'd been banged around, that the surfaces were well worn, and they were throwaway materials. So, he started a series of works in 1970, '71, and when he goes to Graphicstudio in '72, and he takes them with him.”

The printmakers catalogued and photographed the boxes, but that night, the cleaners came in and, believing they were garbage, threw them away.

“When the printmakers came in the following morning, they discover that the boxes are gone,” Dellinger recounted. “They run to the dumpster in the parking lot, but the garbage had already been picked up and taken to the city dump. So the printmakers got the film they'd shot to turn the boxes into prints, and they rush to the landfill with photographs of the boxes they were trying to find, trying to figure out which dump truck had emptied the dumpster at the University of South Florida that morning and where it had dumped its load.”

Remarkably, they found quite a number, which they took back to the studio. But there were others that they were unable to find.

“So, they challenged a ceramicist to reproduce the lost boxes," Dellinger recounted. "They insisted that they had to look like the actual box artwork, but in ceramic form, in clay. It wasn’t easy. They had labels, so they had to come up with lithography that could be put on decals which would be placed on the ceramic pieces to accurately replicate the addresses that the box had been sent to, the name of the company, the cancellation marks and rubber stamps.”

Making the boxes look dirty and weathered was even more challenging.

“Rauschenberg liked that they were dirty old boxes,” Dellinger said. “He liked, in fact he embraced the idea that it was a throwaway material, non-archival, not to be kept forever. But in order to get the appropriate patina, the ceramicists ended up rubbing the oil off their faces and rubbing it onto the surface to both make it dirtier and to give it a little like skin-oil sheen. Everyone working on the project was told not to shower, and each day they did their best to take that gritty oil from their faces and hands and rub it on the ceramic boxes. So all of those pieces have this kind of weird deep dark patina that has to do literally with the printers and the studio assistants wiping their face and hand oils all over the works.”

They knew they were successful when Rauschenberg returned to Graphicstudio and couldn’t tell that the replacements were actually ceramics.

These pieces came to be known as Rauschenberg’s “Made in Tampa” clay pieces, which they editioned.

ROCI

A decade later, Rauschenberg and Saff made that initial trip to China.

“It wasn’t about politics,” said Dellinger. “But Bob believed in spreading a message of peace. And when he announced to the world the ROCI tour, he did it on the floor of the General Assembly of the United Nations.”

“Rauschenberg’s belief in the power of art as a catalyst for positive social change was at the heart of his participation in numerous international projects in the 1970s and early 1980s, and which culminated between 1984 and 1991 with his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI),” states the Rauschenberg Foundation website. “ROCI was a tangible expression of Rauschenberg’s long-term commitment to human rights and to the freedom of artistic expression.”

Still smarting from allegations that the State Department had pressured the Venice Biennale jury to award him the Grand Prize for Painting (now called the Golden Lion) in 1964, Rauschenberg eschewed State Department and corporate sponsorships.

“He could have made it the Pepsi-Cola or Coca-Cola Rauschenberg world tour, or he could have engaged the State Department, and they likely would have sponsored him,” Dellinger noted. “He was such a celebrated artist. But Rauschenberg intended to take his ROCI world tour to countries run by dictators and authoritarians. He was the first western contemporary artist to show in China, in the Soviet Union, in Chile under Pinochet. When he went to Cuba, Fidel invited him to his beach house. He couldn’t do that if the tour was being sponsored by the State Department, maybe not even if Pepsi or Coca-Cola was financing the tour.”

So, Rauschenberg sold his personal art collection, including his Andy Warhol, and financed the trip on his own.

And he and Saff made Graphicstudio the headquarters for the world tour.

That didn’t mean that the tour was without controversy. It was remarkable for an American to be accepted in many of the countries he visited. But Rauschenberg had little concern for politics or political correctness.

“For example,” said Dellinger, “when he showed in China followed by making an exhibition in Tibet, he probably offended his Chinese hosts.”

That notwithstanding, Chinese artists still talk about Rauschenberg’s visit.

“Ai Weiwei and famous Chinese artist Zhu Bing say there was art in China before and after Rauschenberg. His impact on the world stage was immense.”

“At the time, the exhibition is said to have heavily influenced the “85 New Wave,” an important generation of local avant-garde artists who were a key factor in the development of the Chinese contemporary scene,” the Rauschenberg Foundation website notes.

Graphicstudio Legacy

“Graphicstudio and the University of South Florida have an extraordinary history,” Dellinger noted. “I actually curated the last retrospective of Graphicstudio at the Tampa Museum of Art. Its production over many years included more than a hundred visiting artists of international acclaim.”

Rauschenberg was just one.

“He was a very important one and really it's conversations between Don Saff and Robert Rauschenberg that influenced the way that the studio would function more broadly,” said Dellinger. “The Graphicstudio archives have even been housed now and are a part of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. So, while ROCI became a focal point and a major exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington D.C., Graphicstudio also had a major retrospective in the late 1980s at the National Gallery of Art, and they have since not only housed the archive but also acquired work that has been produced by Graphicstudio over all of the decades.”

Rauschenberg would eventually build a bigger and more elaborate print studio in Captiva. As his health declined, he traveled less frequently to Graphicstudio. But Graphicstudio retained an important place in Rauschenberg’s mind and heart.

“He felt deeply grounded here in Southwest Florida and on Captiva because he knew he could always do projects at USF Graphicstudio,” Dellinger observed. “It would be a kind of escape for him.”

Support for WGCU’s arts & culture reporting comes from the Estate of Myra Janco Daniels, the Charles M. and Joan R. Taylor Foundation, and Naomi Bloom in loving memory of her husband, Ron Wallace.