Bob Rauschenberg’s move to Captiva Island may have been ordained by the stars — he had consulted a famous astrologer about a move — but it was the moon that had captured his imagination.

“Rauschenberg, as it turns out, by the late ''60s becomes one of the first artists in residence for NASA," explained Jade Dellinger of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. "It's one of the reasons he ends up moving to Florida. He knew the astronauts when the Apollo 11 mission happened. So, he came to Florida to watch that incredible event in person.”

Rauschenberg associated with many of NASA’s top scientists through a group he’d formed in Manhattan under the name of Experiments in Art and Technology.

“This group made performances where they would be partnering as both artists, composers, choreographers, and dancers with scientists and engineers that were equally of world renown, connected to industry in ways that were interesting,” Dellinger noted.

The group was at a place called Max’s celebrating the lunar landing when one of its members, Forrest “Frosty” Myers, made an observation that abruptly killed the mood. According to Dellinger, Myers said, “We had planted our flag nationalistically claiming the moon, but other than that, we'd really left detritus. We'd left trash on the moon.”

So Myers, Rauschenberg and four other artists made drawings to send to the moon.

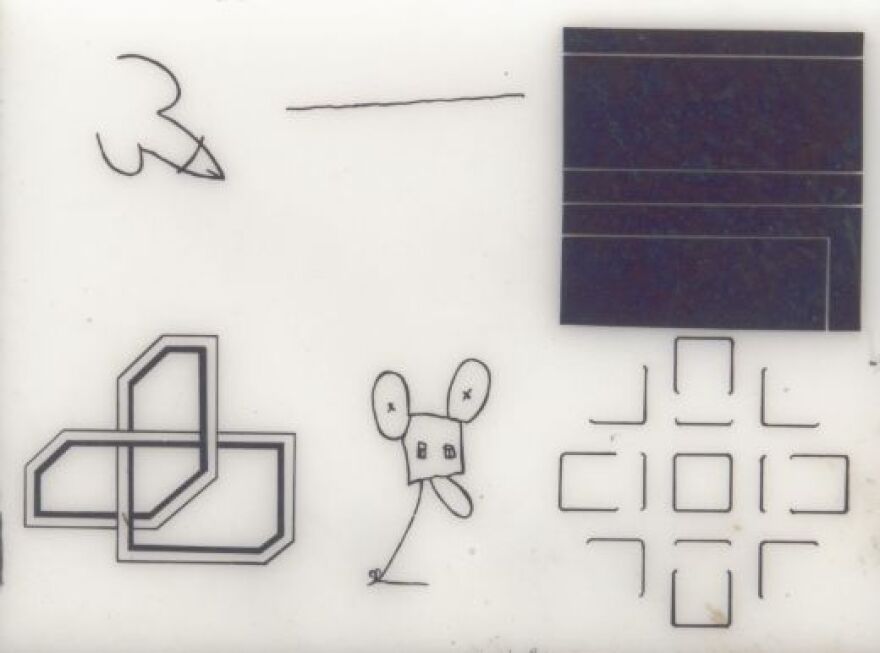

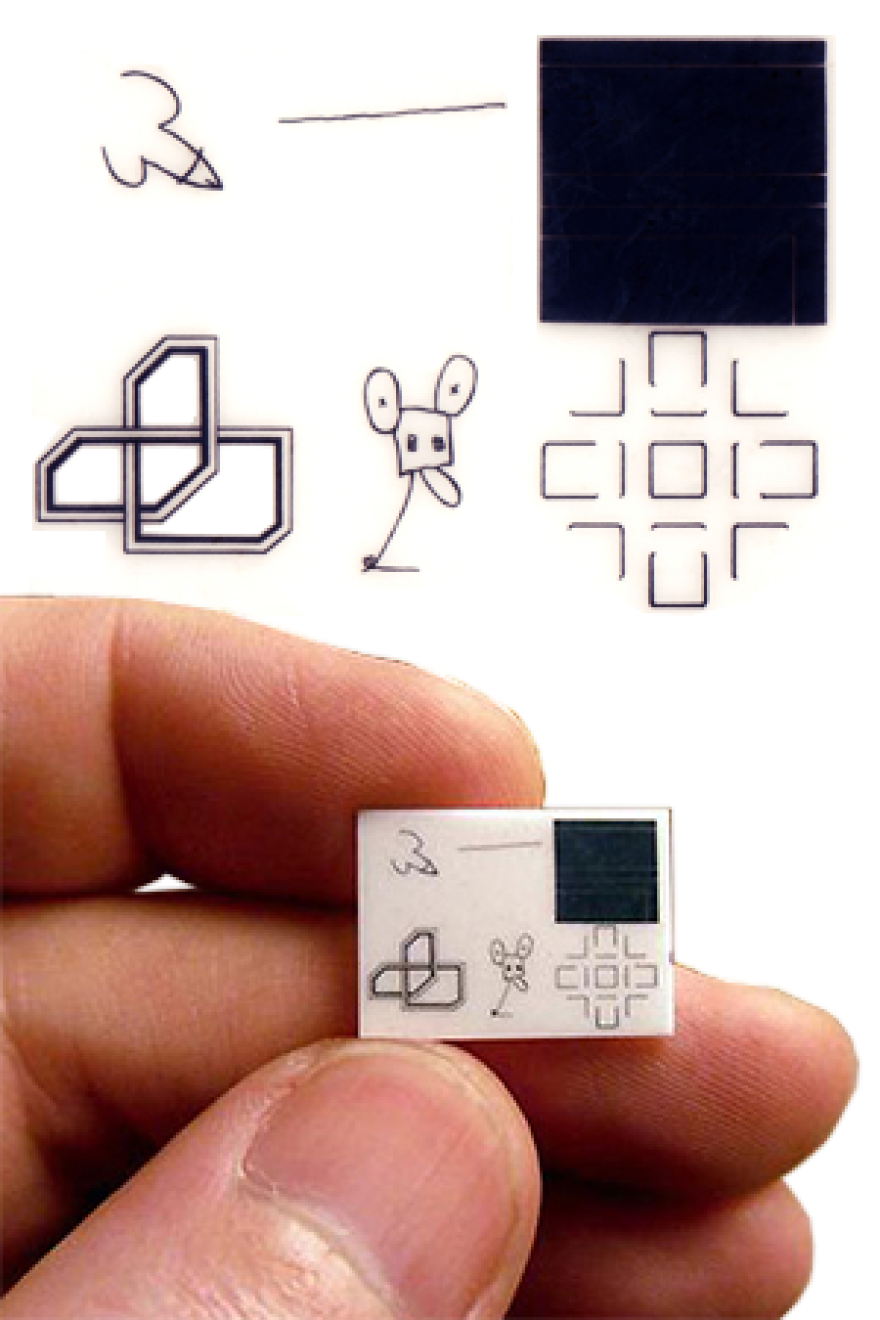

Some scientists at Bell Laboratories transferred the drawings to a ceramic chip about the size of a postage stamp.

Then they asked NASA for permission to give the chip to one of the Apollo 12 astronauts to leave on the lunar surface. But that authorization never came.

“So in the last minute, they sent one of these small chips to be attached to the landing legs of the LEM 6 to secretly, surreptitiously, and without permission send a museum with works of art by Robert Rauschenberg, David Novros, Forrest Myers, John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol to the moon, where it has resided without much fanfare since 1969,” said Dellinger.

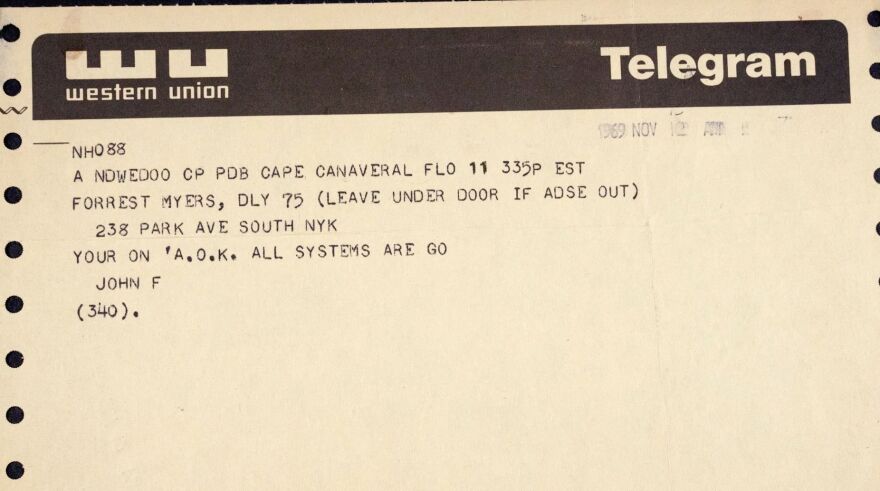

Myers got the confirmation that the chip made it to the moon.

“It was Forrest who initiated the project … through Experiments in Art and Technology, and then who received an anonymous telegram just before the launch of the Apollo 12,” Dellinger noted.

“It was signed, ‘A-OK. All systems are go,’ so that he knew that it had been attached," Dellinger continued. "It was signed John F. Of course, there was no John F. that worked for Grumman. We've been through the Grumman yearbook that would have had the access necessary to actually attach it, but instead, the person who started us on our quest for the moon was John F. Kennedy.”

In all, Bell Labs made 24 multiples of the Moon Museum chip. Each of the artists and engineers got one.

“We’ve really, of the 24, only really located about a dozen,” said Dellinger. “It's the smallest object in the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection. It's in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Rauschenberg's is in his foundation … Claes Oldenburg's remains with his estate. Andy Warhol's is in the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and occasionally on display, and then we think John Chamberlain probably gave his to a girl in a bar and kept asking Frosty for another copy, but never received a second copy.”

MORE INFORMATION:

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)

The Moon Museum would not exist without Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.).

This collective was formed in 1966 by engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer and artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman as a not-for-profit service organization with a goal of promoting collaborations between artists, engineers and scientists.

“E.A.T. was a kind of matchmaking service,” explained Gary Garrels, SFMOMA Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture. “An artist would submit a form that stated what their interest was, what materials they wanted to work with, and what problem they were trying to solve, and the organization would match them with particular engineers and scientists.”

Kluver was a research scientist with Bell Laboratories. Rauschenberg met him in 1960 at an event at the Museum of Modern Art, where Kluver and Swiss artist Jean Tinguely had produced a large kinetic sculpture titled “Homage to New York.”

It was designed to self-destruct with the push of a button. Many New York art world luminaries turned out to see what would happen on the fateful March evening when the thing was to go off in MoMA’s Garden.

Rauschenberg was so intrigued by the concept that he contributed a piece to the spectacle, a small “mascot” called “Money Thrower.”

That meeting led to several collaborations, including “Oracle” (1962–65), a sonic sculptural environment, and “Soundings” (1968), an immersive, voice-activated sound and light installation. Both involved the audience, utilizing their interaction to help “complete” the work.

It also led to the formation of E.A.T.

During the group’s existence, performances were held that incorporated pioneering technology in video projection, wireless sound transmission and Doppler sonar.

It was the era of the space race and new frontiers. Beginning with his combines in the 1950s, Rauschenberg had a keen interest in technology and was ever on the hunt to find new ways to integrate technology into his artistic endeavors.

“In this period, the ‘60s, Rauschenberg does this event called ‘Nine Evenings: Theatre and Engineering,’” observed Dellinger. “John Cage, Merce Cunningham, incredible group of people, artists and scientists, sort of being paired together. It's about art and engineering, and this leads to his establishing Experiments in Art and Technology, this group that includes scientists and artists with the idea that with this collaborative spirit, scientists would become potentially more open-minded about ideas and creativity, and that artists would have opportunity to realize projects that, as absurd as some may have seemed, they could only be done with some advanced technology.”

One such absurd performance piece was “Mud Muse.”

“If you ever get to Stockholm, or actually, if you just get on YouTube, there's some great video of this bubbling ‘Mud Muse,’” Dellinger continued. “The idea was to do a sort of horizontal painting of mud, but that it would be interactive, that as people moved in the room, they would engage it, but also the mud would be bubbling, and it seems so simple, but it's incredibly complex in that the viscosity of the mud was super important, and all of these things took a lot of research.”

“Mud Muse” is a room-size aluminum-and-glass vat that holds thousands of pounds of mud. Not just any mud, but a special recipe made with bentonite, mixed to a specific viscosity that bubbles along, stimulated by pulsing air valves beneath its surface, to a prerecorded soundtrack playing on a nearby 1960s reel-to-reel.

“This was the sort of project that Experiments in Art and Technology was trying to take on,” said Dellinger. “And because of Kluver and Waldhauer’s connection to the Apollo mission and his appointment as artist in residence for NASA, Rauschenberg embarks on a series of lithographs that he called the ‘Stoned Moon Series’ which use NASA-related imagery.”

As a result of these connections and this work, Rauschenberg was invited to attend the launch of Apollo 11.

He wrote in a journal, “It was breathing now half asleep. Relaxing with fueling. The moon rose. My head said for the first time, the moon was going to have company.”

The Moon Museum Operation Turns Clandestine

Back in New York, many of E.A.T.’s members gathered at a club called Max’s where Andy Warhol liked to entertain. After Frosty Myers made his comment about only leaving a flag and some garbage on the lunar surface, he and Rauschenberg famously proposed that they send art to the moon on the next Apollo mission.

At first, the scientists scoffed, pointing out that Myers made large-scale sculptures and with payloads, every ounce counts. But they countered that if Myers could reduce his work to a drawing, the Bell Labs folks could place it on a small, lightweight transistor and propose to NASA that it be included in one or the astronaut’s personal preference packs.

“The personal preference pack was what the astronauts would carry with them,” Dellinger explained. “It was sort of a pocket for whatever the astronaut wanted to carry into space, whether a roll of stamps, cuff links or small American flags that they would roll up to give away later as souvenirs. All of those items would be individually photographed, tested for magnetic properties or anything that could do damage to their effort to make it to the moon.”

Kluver, Myers and Rauschenberg were confident that NASA would approve the tiny ceramic chip that included their drawings.

According to Dellinger, the Bell Lab scientists worked on making the ceramic wafers as an after-hours moonlighting project.

“Rauschenberg and Forrest 'Frosty' Myers didn't want to make it solely about themselves,” said Dellinger. “They had a collective of very important, noteworthy artists that they decided to invite. They each, knowing then that Bell Laboratories had the transistor team, they had actually made the first transistors, they were essentially making micro circuitry, that if they each made a drawing, they could collect the drawings and put them onto a small ceramic wafer, like a microchip, like a computer chip, with each of the drawings and create their own museum for the moon.”

Much to their surprise, they did not get any response from NASA to their request to include the chip in one of the astronauts' personal preference packs.

So as Apollo 12’s launch date approached, one of the scientists at Bell Laboratories sent the chip to an engineer friend at Grumman who was working on the Apollo 12's LEM (Lunar Excursion Module). That engineer hid it in the Kapton foil insulation that lined the LEM’s legs.

The Grumman engineer who planted the chip on the Apollo 12 LEM never came forward. If his name is known, none of the artists or engineers involved in the operation has ever revealed his identity.

The Apollo 12 mission was organized to collect seismologic, scientific and technical data from the moon. The mission was flown by astronauts Alan Bean, Charles “Pete” Conrad and Richard Gordon. Although they did not know it at the time, Bean, Conrad and Gordon also became the first museum curators in space.

Rauschenberg’s Moon Museum drawing was a straight line

“Each artist has a remarkable story in terms of the way and the reason, the rationale for the work that they made,” observed Dellinger.

Rauschenberg drew a simple line as his contribution to the Moon Museum.

“For Rauschenberg, all that was necessary was for him to make a mark with a pencil,” Dellinger explained. “So, he initially drew on a small, maybe five by seven-inch piece of paper, just this very simple line and signed it RR.”

It was something of a full-circle moment as well.

In 1953, he created “Automobile Tire Print.” It resulted from a collaboration with musical composer John Cage (1912–1992).

As Cage drove his Model A Ford in a straight line over twenty sheets of paper that Rauschenberg had glued together and laid in the road outside his Fulton Street studio in Lower Manhattan, Rauschenberg poured a pool of paint on the ground for the rear tire to pass through. It left a black tread mark that stretches in a diminishing line along the 22-foot length of paper.

Over the years, “Automobile Tire Print” has been interpreted as a monoprint, a drawing, a performance, a process piece, and a distinctive exploration of indexical mark making.

“For Rauschenberg, the simplicity of this minimalist gesture was all that really mattered to him,” said Dellinger. “It wasn't about sending a recognizable image aside from the idea that, conceptually, he was making his mark literally on the moon.”

But “Automobile Tire Print” has also been interpreted as one of the earliest examples of Rauschenberg’s interest in the visual and psychological dimensions of temporal experience, themes he revisited in works such as “Hiccups” (1978) and “The 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece” (1981–98).

On a deeper plane, his Moon Museum line could be a profound commentary on Western civilization’s embrace of linear perspective with finite beginnings and endings as opposed to the astrological and Cherokee beliefs that the universe is cyclical and that all sentient beings, along with trees, rivers, stones and mountains are intertwined and interdependent.

Although he kept his multiple of the Moon Museum at his compound on Captiva, Rauschenberg neither spoke of nor exhibited it.

Except one time.

“It's an amazing story, actually, that we've just recently learned through the foundation as they've gone through his papers,” Dellinger said. “Lawrence Voytek worked for Bob for almost 30 years as his studio assistant. One day, Voytek’s daughter wrote out a little questionnaire for Bob to complete for one of her [junior high school] classes. One of her questions was, ‘Given that 'The ¼ Mile or 2 Furlong Piece' is surely the biggest you've ever made, being a quarter mile in length, what's the smallest work of art you've ever made?’ And he wrote back to her saying, ‘I've hidden a work of art on the Moon, and it's the smallest work I've ever made, and it's for future discovery.’”

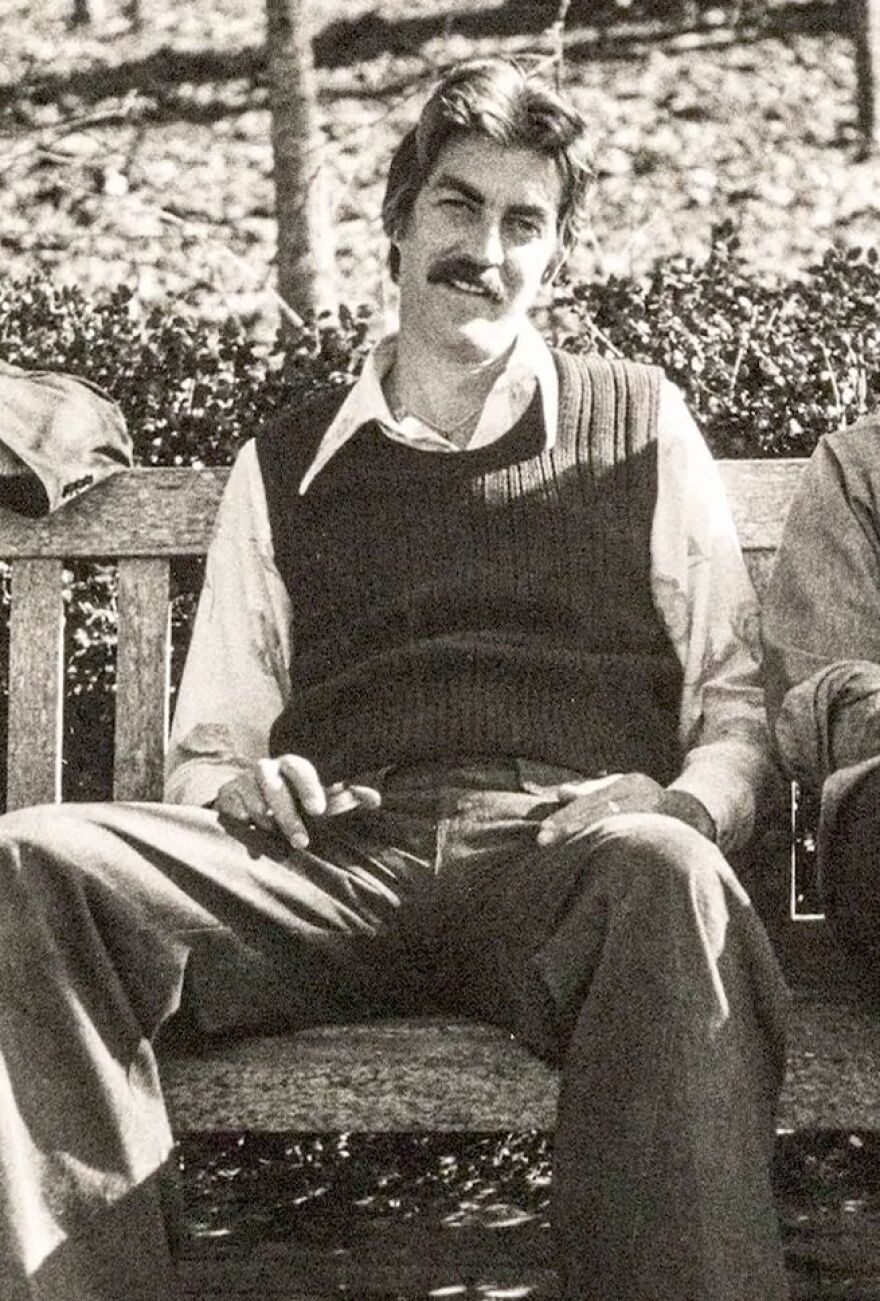

Forrest “Frosty” Myers' drawing based on sculpture that befuddled MIT

Myers explained his contribution to the Moon Museum to Dellinger in a conversation they had on March 28, 2009.

““[My contribution is] a drawing for (or related to) a sculpture …. I was involved with a collective of artists, including Mark DiSuvero, who started the Park Place Gallery [in the SoHo region in Manhattan]. We exhibited together often in the mid-1960s, and were invited to participate in a group show at MIT during this period. I presented a large (perhaps 7 feet high) metal sculpture in the exhibition. It was deceptively simple. At first glance, it appears to be aligned geometric forms, but upon closer inspection, you realize that the forms are interlocking and that they are derived from a continuous line.”

Myers told Dellinger that when the work was being installed, he was approached by several students and then by their professors.

“Astonished by my sculpture, they confessed that my work was a precise physical manifestation of a computer rendering they had spent the entire semester plotting. They had been contemplating some complicated mathematical problem by assigning coordinates to create a virtual object that was identical to the sculpture I had created for the exhibition.”

This was at a time when PCs, tablets, Photoshop, Paint Box and other illustration programs were yet to be conceived.

“The MIT computer didn’t even have a mouse,” Myers noted. “They were using something that looked like a joystick but, much to my surprise, they were able to take my sculptural form and manipulate it in virtual space. With their primitive joy stick, you could rotate and spin my sculpture effortlessly – as if it were floating in a zero-gravity environment. They made the form weightless, and could stop motion with equal ease. The ‘computer drawing’ I included on the Moon Museum was, in fact, one of several screen-captures taken with a Polaroid camera.”

Thus, Myers’ Moon Museum drawing is a two-dimensional representation of a sculptural form that was plotted in virtual space by the MIT team independently of Myers’ 3D sculpture.

“They had created this form through tedious computation and were very curious to know how I had visualized mine,” Myers told Dellinger. “They kept asking me to reveal exactly how, as a sculptor, I had come to the same basic solution."

So, Myers' contribution had to do with making one of the first computer drawings based on a sculpture.

Myers is regarded as one of the pioneers of the SoHo art district of the 1960s. He was a founding member of the Park Place Gallery, the first gallery in the neighborhood. He also designed Max’s Kansas City, a bar where artists working in different genres could meet and debate ideas and where the E.A.T. crew convened to celebrate the lunar landing.

Visit https://forrestmyers.com/ to view Myers’ biography, as well as lists of his solo, two-person and group exhibitions along with the museums and public collections that have examples of his work.

Andy Warhol contributed calligraphic spiggle

In 1969, Myers described Warhol’s Moon Museum drawing to New York Times reporter Grace Glueck as “a calligraphic spiggle made up of the initials of his signature.”

Those were more genteel times, and some postulated the drawing was, a’ propos, a rocket ship.

In 2009, Myers fessed up, bluntly characterizing the drawing as “Warhol’s now infamous ‘AW’ penis sketch.”

But Myers is quick to add that it would be easy to dismiss Warhol’s drawing “if you don’t know [his] work.”

Ascribing meaning to the calligraphic rendering is as multi-layered as Warhol’s overall oeuvre of work, and what Warhol actually meant to convey will remain a matter of conjecture – which is appropriate, given that throughout the course of his career as a fine artist, Warhol refused to explain his work, famously declaring that all you need to know about him and his work is already there “on the surface.”

On one level, the use of phallic imagery could simply signify that Warhol saw himself as the father of the Pop Art movement. Indeed, he was referred to as the “Pope of Pop Art.”

However, Warhol assiduously avoided drawing attention to the fact that he was a devout Byzantine Catholic who at times attended services on a daily basis.

“Father of Pop Art” would have been an appellation with which he was far more comfortable. In this regard, Warhol clearly pioneered the Pop movement, not only in art, but in sculpture, photography, film, literature and even music (where he produced the band Velvet Underground). He influenced a host of celebrities, endorsed products, appeared in commercials and made frequent guest appearances on television shows and in films. He appeared in everything from “Love Boat” and “Saturday Night Live” to the Richard Pryor movie “Dynamite Chicken.”

From the time of MoMA’s Symposium on Pop Art in December 1962, it became increasingly clear that there had been a profound change in the culture of the art world and that Warhol was at the center of that shift.

Warhol was the one whose work made the cleanest and most radical break with previous art — a rupture that demonstrated the single-mindedness of his conception and the way in which his themes and motifs resonated with the spirit of America’s postwar consumer society. So, Warhol can be forgiven if he meant his Moon Museum iconography as an acknowledgement of his seminal role in creating and promoting pop culture.

Some regard Warhol’s drawing as frivolous. But Warhol used frivolity as counterpoint to the lofty and serious discourse embraced by the Abstract Expressionists of his day. To their horror and the disgust of most of the art critics of the 1960s (who often derided him as a hoax or “put-on”), Warhol eschewed conventional artistic motifs in favor of the ubiquitous imagery found in popular culture and the mass media. Thus, celebrity photos from magazines and tabloids, advertising graphics for mass consumer products, and underground comics all became “grist for Warhol’s roving, omnivorous imagination, which transmuted these images into art without altering much of its essential character as visual kitsch,” as one Warhol biographer notes.

It is also possible that Warhol employed the penis imagery philosophically.

Through the use of silk screens and a bevy of assistants, Warhol mass-produced artwork that unabashedly incorporated mass-produced products such as Brillo, Campbell’s Soup cans and Coca-Cola, as well as Hollywood-produced stars like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor.

Taking pains to minimize the role of his own hand in the production of his art, he would conceive an idea and then oversee or delegate its execution. As he refined this approach, his Factory in Manhattan evolved from an atelier into an office, with Warhol becoming a brand and the essence of the Pop Art movement.

Warhol had a tradition throughout much of his career of producing erotic photography and drawings. His portraits of Liza Minnelli, Judy Garland and Elizabeth Taylor as well as films like “Blow Job,” “My Hustler” and “Lonesome Cowboys” draw from gay underground culture and openly explore the complexity of sexuality and desire. The first works that Warhol submitted to a gallery were homoerotic drawings of male nudes. They were rejected for being too openly gay, which may have prompted Warhol to wryly place a rendering of a penis on the moon, where it could look down on Manhattan and all the provincial, parochial galleries, gallerists and dealers who were so behind the times.

It is also possible that his penis drawing was intended as a rejoinder to Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who found Warhol “too swish” for their liking.

“There was nothing I could say to that. It was all too true,” Warhol wrote at the time. “So I decided I just wasn’t going to care because those were all the things that I didn’t want to change anyway, that I didn’t think I ‘should’ want to change… Other people could change their attitudes, but not me.”

If Forrest Myers knows why Warhol chose to include a penis-shaped rocket made out of his initials on the Moon Museum, he hasn’t said … at least not publicly. But then again, if Warhol wouldn’t have disclosed his true meaning, why should Myers or anyone else?

Claes Oldenburg put Mickey Mouse on the moon

OK, so maybe the mouse depicted by artist Claes Oldenburg in his Moon Museum drawing is not of Mickey Mouse, or even Minnie. But his iconic Geometric Mouse kite was derived from Mickey and directly related to the large-scale sculpture he had at the Museum of Modern Art at the time he did the rendering for the Apollo 12 mission.

“There was something a little absurd about sending a cartoon to the moon,” Moon Museum founder Forrest Myers conceded in Dellinger’s 2009 interview.

“[Oldenburg] had actually gotten into trouble with Disney,” Dellinger pointed out. “They were trying to sue him over his efforts to make his own sort of artistic vision for Disney, and when Myers invited him to participate in the Moon Museum, he leapt at the chance to one-up Disney. So he rendered a drawing of his Geometric Mouse with a kite, so it's escaping gravity, so it looks grounded or tethered as it escapes gravity. So, in the end, he [did] trump Disney in that his version was the first to make it to the moon.”

Oldenburg was one of Pop’s most widely admired artists in 1969. When he first arrived in New York City in 1956, he fully expected to make his mark in the art world as a painter. But by 1960, he had come to realize that sculpture offered the best means for upending the art of his time.

“The results,” concluded the New York Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with an Oldenburg retrospective it exhibited in 2013, “are some of the most audacious and provocative art objects of the twentieth century.”

“I’d like to get away from the notion of a work of art as something outside of experience, something that is located in museums, something that is terribly precious,” Oldenburg declared in 1960.

Culling his subject matter from the clothing stores, delis, and bric-a-brac shops that crowded Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Oldenburg’s store sculptures depicted everyday items like shirts, dresses, cigarettes, sausages, and slices of pie.

“Oldenburg made them from armatures of chicken wire overlaid with plaster-soaked canvas, using enamel paint straight from the can to give them a bright color finish,” noted MoMA. “At the gallery, the reliefs hung cheek by jowl, emulating displays in low-end markets.”

Oldenburg switched before long to sculptures composed of fabric. Oversized soft sculptures such as his “Floor Burger,” “Floor Cake” and the 17-foot-long “Floor Cone” were hailed as groundbreaking artworks.

“Their soft, pliant, and colorful bodies challenged the convention that sculpture is rigid and austere, and their subject matter and colossal scale infused humor and whimsy into the often-sober space of fine art,” MoMA related. “With this work Oldenburg proposed an alternate form of monumental sculpture, saluting subjects from contemporary American life.”

But a new motif captured Oldenburg’s fancy soon after he moved his studio in 1965 to a loft on Fourteenth Street in Manhattan.

That’s when Oldenburg began playing with the image of Walt Disney’s animated cartoon, Mickey Mouse.

Oldenburg’s iteration combined Mickey’s form with that of an old movie camera whose square box and two circular film spools mimicked the famous mouse’s face and ears. Oldenburg dubbed his version “Geometric Mouse,” which he suggested was his alter ego, stating one time, “The Mouse, that’s me!”

Oldenburg began incorporating Geometric Mouse into everything he did. He used it as a symbol on the letterhead for his 1966 retrospective exhibition at The Moderna Museet in Stockholm. He used it as the logo on a banner advertising his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1969. He even tried to convince the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago that it should redesign its facade in the shape of a geometric mouse (which the museum declined, of course).

When Forrest Myers approached him about including a sample of his work in an art museum he was secretly planning to send to the moon with the help of engineers at Grumman Aircraft and scientists at Bell Labs, Oldenburg immediately offered a drawing of Geometric Mouse for the clandestine project.

But Oldenburg did not rest on his lunar laurels.

In 1972, Oldenburg took his Mouse Museum to an international art exhibition in Kassel, Germany. Five years later, Oldenburg actually built a museum in the shape of Geometric Mouse using black-painted wood and corrugated aluminum for its walls.

Both Mouse Museums housed some 385 objects consisting of kitsch, toys, souvenirs, and prototypes for his own artworks. He selected the latter from his collection of more than a thousand such items. He arranged them in a loosely associative sequence, devoid of any judgment about their relative importance.

Oldenburg’s second wife and collaborator, Coosje van Bruggen (1942–2009), wrote that the collection offers a glimpse into Oldenburg’s working method and his perception of American society. By treating the included object in “a nonhierarchical way,” each maintains its own unique identity.

“The collection represents many of the artistic questions that Oldenburg has dealt with throughout his career: unexpected scale, mutated forms, low art as high art, found objects, and alternatives to the traditional museum or gallery experience,” stated the Guggenheim in connection with an exhibition of the 1977 Mouse Museum that it staged from October 30, 2012 to February 17, 2013.

In the final analysis, Oldenburg regarded Geometric Mouse as a symbol of analysis and intellect, “autobiographical but not necessarily a portrait…[I]n other words, the mouse is a state of mind.”

Davis Novros never acknowledged his Moon Museum drawing

Novros was an intriguing choice for inclusion in the Moon Museum. In 1969, he was at the very beginning of his career, not far removed from the days in which he worked as a carpenter at both the Museum of Modern Art and a coop of artists called Park Place.

Myers met Novros at a launch party thrown by James Rosenquist. Novros was known for wall murals at the time, and Myers took an immediate liking to his work. He admired how Novros used shapes that moved across a section of wall in a way that encouraged viewers to do the same.

“I used colors that changed as you walked along, the Murano colors [a powdered pigment which is suspended in clear lacquer], and even before that, metallic colors and other things,” Novros told Michael Brennan in an October 2008 interview for the Smithsonian Institution’s “Archives of American Art.

He also employed materials and spray-painting methods that made the paintings appear to shift in light.

“I was trying to make paintings that could be seen by people in motion, and by light that was in motion. Not a fixed kind of gallery concept,” Novros told art writer Tom Butter in 2009.

Myers not only pushed Novros’ paintings, but also hooked him up with Mickey Ruskin just as the latter was opening Max’s Kansas City.

Ruskin needed someone to spray paint the plastic booths in the bar black and Novros did the job in one night. Ruskin bought two of Novros’ paintings, and Novros became a regular, meeting future Moon Museum collaborators John Chamberlain (from whom “I really learned about risk”) and Andy Warhol in the popular artists’ hangout.

Perhaps it was their personal friendship, or that Myers had a premonition that Novros was destined to launch a groundbreaking career in fresco and placemaking soon after the launch of Apollo 12. Whatever the explanation, Myers extended the Moon Museum invitation to Novros who, in 1969, was still looking for his “voice” while making large, abstract paintings on irregularly shaped, multi-paneled canvases with sensuous and reflective surfaces created with multiple layers of Murano-glazed, brush-applied acrylic pigment that provided viewers with new types of perceptual and emotional experiences.

“Even though they were in units, in pieces,” he explained during the Smithsonian interview, “they were like portable murals” that sought to communicate content through monochromatic color, geometric form and complex spatial issues that encouraged a kinesthetic viewing experience through the surface’s response to changing light.

“If you dramatically enlarge David’s drawing, you will have a good idea about how his paintings looked back then,” Myers told Dellinger in March of 2009. “The white lines in the drawing were the spaces that separated the panels in his large-scale works. David’s paintings were architectural.”

This architectural aspect is precisely what Novros would have most wanted to convey to space explorers or future generations of earthlings that might happen upon the Moon Museum in the Ocean of Storms.

For Novros, large-scale work like his movable murals and frescoes uniquely empower the viewer to commune with the paintings, to get in motion with the work, to become absorbed in the painted world. And they have this effect because they are non-pictorial, because the content is not confined by a delimiting rectangle.

Ironically, the Moon Museum project tasked Novros with the seemingly impossible challenge of conveying his expansive view of art in one corner of a tiny ceramic chip that is, in the final analysis, the very type of object that Novros eschewed and spent a lifetime trying to transcend.

Interestingly, Novros never mentioned the Moon Museum in any of the many interviews he gave later in life.

According to Dellinger, he gave his Moon Museum duplicate to his father and it was not discovered after his dad’s death among the numerous reviews and other mementoes that his proud father had kept unbeknownst to Novros.

Novros has exhibited in several prominent venues, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Dallas Museum of Fine Art in Dallas, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and the Bremen Museum of Modern Art in Bremen, Germany.

2014 Moon Museum exhibition at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery.

John Chamberlain’s grid drawing

At the time of the Moon Museum project, John Chamberlain was at the apogee of his fame and critical acclaim. He had built a reputation as the Manhattan bad boy who crafted vibrantly colored, dynamic sculptures from crushed, twisted and bent automobile parts. His work had been included in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1961 “The Art of Assemblage” exhibition, the 1964 Venice Biennale and several Leo Castelli Gallery shows. And, inspired in part by his friend Andy Warhol, Chamberlain began directing films in 1968 that included “Wedding Night,” “The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez” and “Wide Point.”

“Everyone knew Chamberlain’s compressed metal sculptures, but he couldn’t really contribute a full-sized crashed car for the Moon Museum,” quipped Myers in is 2009 interview with Dellinger. “[But by then] John … was candy-apple spraying (with an automotive finish) grids on small – maybe 12-by-12-inch – squares. The grid drawing [on the Moon Museum chip] is quite like the metal template that John was using at the time to make his panel paintings. He would paint the background color, then spray the grid of boxes with a metal-flake paint using the cut-out. It is possible that the ink drawing he made for the Moon Museum was simply traced from his stencil. It looks a lot like the outline of a stencil, and he did a number of paintings with the same basic structure.”

Even today Chamberlain is commonly associated with the powerful large-scale sculptures he made from automobile parts. But by the late 1960s, he had shifted to other mediums and materials, including two-dimensional paintings made with automobile paint. But he continued expanding his sculptural work, creating a series of white and chrome sculptures as well as others using ephemeral brown paper bags, Plexiglas or aluminum foil.

He returned to automobile parts as his primary material in 1974, creating wall reliefs and freestanding sculptures in both small and monumental scales. While continuing in this direction, he also began working with still photography, an interest that continued until his death in 2011.

“Critics often saw his crumpled Cadillacs and Oldsmobiles as dark commentaries on the costs of American freedom, but Mr. Chamberlain rejected such metaphorical readings,” wrote New York Times journalist Randy Kennedy in his December 21, 2011 memoriam following the artist’s death. “He turned to making sculpture from other things partly because he grew so tired of the automotive associations.”

“It seems no one can get free of the car-crash syndrome,” he told the curator Julie Sylvester in 1986. “For 25 years I’ve been using colored metal to make sculpture, and all they can think of is, ‘What the hell car did that come from?’ ”

Chamberlain had his first retrospective in 1971 at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. A second retrospective was organized in 1986 by the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art.

His numerous honors included the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture in 1993, the Lifetime Achievement Award in Contemporary Sculpture from the International Sculpture Center in Washington, D.C. in 1993, The National Arts Club Award (New York, 1997), the Distinction in Sculpture Honor from the New York Sculpture Center in 1999, and a honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from the College for Creative Studies in Detroit the year before his death.

As these awards and accolades attest, Chamberlain devoted his long and illustrious career to challenging traditional notions of sculpture and to eroding the boundaries between sculpture and painting by placing color on an almost equal footing with form.

In contradistinction to the planned, methodical, often monotone or colorless approach employed by most sculptors of his day, Chamberlain brought an Abstract Expressionist gestural quality to his work, which took on a sudden, unexpected randomness that even his most ardent admirers frequently found unsettling, prompting art critic Peter Schjeldahl to write one time, “the mangle is the message.”

It seems somewhat incongruous that the design Chamberlain chose for the Moon Museum is tight, orderly and likely traced from a stencil.

Chamberlain would chuckle at the question implicit in the previous statement. “Everyone always wanted to know what it meant, you know: ‘What does it mean, jellybean?’ ” he told Julie Sylvester, adding: “Even if I knew, I could only know what I thought it meant.”

Dellinger got his Moon Museum multiple after spotting it on eBay

Dellinger’s Moon Museum multiple traces its lineage to one of the engineers who participated in the project. After he died, his family listed it for sale on eBay.

“I wrote to them immediately and said this is not an appropriate place to try to sell this,” said Dellinger. “I suggested that we should really develop some projects telling its history and maybe providing some context for it, which we've had the great pleasure of being able to do over the years.”

But the family was not inclined to exhibit the chip. They were also not interested in selling it at auction at Christie’s or Sotheby’s. So they agreed to a price that Dellinger happily paid.

Since then, he’s exhibited the Moon Museum multiple both locally and abroad.

It was the centerpiece of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery’s 2014 exhibition “The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission” (August 22-September 27, 2014).

“Rauschenberg kept his copy on Captiva Island, but had never shown it here,” Dellinger noted. “I was looking for a way to re-introduce Bob locally, some six years following his death. This seemed a perfect way to extend his legacy.”

The exhibition at Florida SouthWestern State College followed a Moon Museum exhibition that Dellinger curated in Tbilisi, Georgia, in 2013. He has also travelled the ceramic chip to exhibitions in Venezuela and Ukraine.

As part of Rauschenberg’s centenary, Dellinger is taking the Moon Museum chip to lectures, most recently at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Jacksonville and the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota.

Moon Museum not the only art on the moon

The Moon Museum is not the only art on the moon.

Less than two years after Intrepid landed in the Ocean of Storms, Apollo 15 Commander David Scott placed a 3½-inch-tall aluminum sculpture in a crater near his parked lunar rover in moon’s Hadley-Apennine region, between a meandering gulley and a range of steep mountains. Cast by Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, “Fallen Astronaut” pays tribute to all the astronauts and cosmonauts who lost their lives during the space race between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

In “The Sculpture on the Moon: Scandals and Conflicts Obscured One of the Most Extraordinary Achievements of the Space Age,” American Science’s Acting Editor Corey S. Powell and Emmy-nominated filmmaker Laurie Gwen Shapiro write that Van Hoeydonck flew to Cape Kennedy to pitch the idea to NASA of placing sculpture on the moon at the urging of Louise Tolliver Deutschman, the director of the New York gallery that represented von Hoeydonck and his work. Once there, however, the sculptor ran into the same bureaucratic wall that prompted exasperated New York artist Frosty Myers and Bell Labs scientist Fred Waldhauer to induce a Grumman Aircraft technician to secretly slip the Moon Museum ceramic wafer onto the Apollo 12 lunar lander without NASA’s knowledge or permission.

In Hoeydonck’s case, he met a guy who arranged for him to have a casual dinner at a Cocoa Beach restaurant with the crew of Apollo 15.

Van Hoeydonck and Commander Scott hit it off from the outset. They discovered that they shared obsessions with archaeology and Mayan mythology. By night’s end, the crew members toasted the star-struck sculptor and promised to “get him a sculpture on the moon.”

But the Apollo 15 crew had very definite views of what they wanted that sculpture to be.

“We came up with the idea of recognizing the guys who’d died in the pursuit of space,” Scott told Powell and Shapiro for their Dec. 16, 2013, piece. “We also wanted to recognize our Soviet colleagues as well,” a remarkable sentiment at the height of the space race.

That was not the only restriction Scott and his crew placed on the sculptor.

“Fallen Astronaut” had to be small, unisex, raceless and able to withstand extreme temperature swings, where the highs during the day could reach 250 degrees Fahrenheit and lows at night could plummet to -250 F as well.

Hoeydonck complied, fabricating a lightweight 3½-inch aluminum abstract figurine that Scott secreted aboard Apollo 15. And during his last lunar excursion, he found a home for "Fallen Astronaut" and an associated plaque as well.

“Irwin distracted Mission Control in Houston with inane chatter while Scott took a few bounding steps north from the lunar rover and made ‘Fallen Astronaut’ a citizen of the moon,” Powell and Shapiro report. “He pulled ‘Fallen Astronaut’ from his oversize pocket, placed it directly on the moon dust, and nestled the memorial plaque next to it. A spiritual man who keeps his faith private, Scott treated the dedication of ‘Fallen Astronaut’ as a wordless funeral service.”

Scott mentioned “Fallen Astronaut” just once after returning to Earth – in the post-mission press conference. And he failed to name van Hoeydonck as the sculptor’s creator.

“Nor did the official NASA press release that followed. Scott preferred to keep it that way—treating ‘Fallen Astronaut’ as an anonymous memorial.”

Von Hoeydonck was upset that he couldn’t mention, never lone take credit, for the achievement of placing a work of art on the moon’s surface. He was beyond dismayed that Scott had named his sculpture “Fallen Astronaut” rather than “Gateway to the Stars,” the name van Hoeydonck had intended and preferred.

After the Smithsonian Institution asked the Apollo 15 crew to have their “workman” cast a replica for the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, van Hoeydonck decided to go on CBS News with Walter Cronkite and announce to the world that he was the artist whose sculpture now looked down on the Earth from the surface of the moon.

“In the VIP area, there’s Jordan’s King Hussein and the two Nixon girls, Vice President Agnew, the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and the Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, the only artist with work on the moon,” began Cronkite, unaware of the Moon Museum and the fact that Pop Art and Modernist icons Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Frosty Myers also had works of art on the moon.

“Van Hoeydonck, clutching a ‘Fallen Astronaut’ replica and sporting a white jacket and tie, explained his motivation in creating the sculpture,” recount Powell and Shapiro. “’I thought of the future of man, that the only possible future of man was in the stars.’ He started to describe ‘Fallen Astronaut’ as the ‘smallest memorial on Earth.’ Cronkite cut him off: ‘—not on Earth, though. Smallest memorial in the universe. And there it is. That’s the way they left it.’”

Two weeks after the Cronkite interview, van Hoeydonck told The New Yorker that “amid all the debris of technology left in space, it is the only sign of man’s arts,” expressing a sentiment voiced two years earlier by Frosty Myers, who wanted to leave something more inspiring on the moon’s surface than space detritus.

Van Hoeydonck thought that the news would make him bigger than Picasso. To his chagrin, people hated the idea that an art “outsider” represented by a second-tier gallery had possessed the temerity to place the first and only sculpture on the surface of the moon.

Interestingly, one of van Hoeydonck’s most vociferous detractors was New York Times art critic Grace Glueck, who broke the story about the Moon Museum within days of the return of Apollo 12.

“Writing in the April 22, 1972, edition of the New York Times, influential art critic Grace Glueck sniffed that the moon sculpture ‘resembles nothing so much as a swollen tuning fork,’” Powell and Shapiro report. Inexplicably, she apparently made no mention of the fact that a group of six prominent New York artists had beaten van Hoeydonck to the moon.

The rift between van Hoeydonck worsened over the years, as the Powell and Shapiro article describes in delicious detail, with accusations from numerous sources denigrating van Hoeydonck for profiteering and commercial exploitation of the nation’s flights to the moon. Using van Hoeydonck’s experiences as a benchmark, Myers and his Moon Museum colleagues were wise to keep their involvement quiet in the decades that followed the Apollo 12 mission and refrain from publicizing or commercializing the art they’d placed on the moon.

For all their copious research, detailed analysis and lengthy reporting about Paul van Hoeydonck and the “Fallen Astronaut” sculpture, it is simultaneously curious, amusing and disturbing that Powell and Shapiro either did not know of the Moon Museum at the time they published their piece or chose, for whatever reasons, not to mention it.

Damien Hirst, Stephen Little may have art on Mars

Two artists may have landed artwork on Mars.

On June 2, 2003, the European Space Agency launched the Mars Express, an orbiter that included a lander named The Beagle 2 (named in tribute to the ship that twice carried Charles Darwin during the expeditions (to the Galapagos Islands and other destinations) that ultimately lead to the theory of natural selection. Bolted to the lander was a 3-by-3-inch aluminum plate containing a painting consisting of 16 multi-colored spots that, on cursory glance, resembled a child’s watercolor box.

Created by artist Damien Hirst, this spot painting also had a functional purpose. The aluminum plate was designed to calibrate the lander’s X-ray equipment. The colors Hirst included in the painting were chosen to check and calibrate the lander’s camera. And the minerals in the pigment were supposed to correct the sensor measuring the soil’s iron content.

Beagle 2 began its descent to the Martian surface on Christmas morning, 2003. A safe and successful landing necessitated three interrelated steps. First, friction from the Martian atmosphere had to slow Beagle 2 to a pre-determined target speed. At that point, sensors within Beagle 2 would deploy parachutes to further slow the lander’s descent. Then, at about a mile above the surface, large gas bags would inflate to cushion the landing as Beagle 2 bounced along the red planet’s surface. After Beagle 2 finally came to rest, the gas bags were to deflate, allowing the top of the lander to open, thereby exposing four solar array disks and a UHF antenna. The latter was programmed to send a signal (and possibly an image of the Martian surface) back to Earth.

Beagle 2 was scheduled to land at 2:54 p.m. on Christmas Day and make its initial transmission about 5:30 UT. Another transmission was to occur the next (local) morning to confirm that Beagle 2 survived the landing and the first night on Mars. But no signal was ever received and, a month later, the European Space Agency declared the Beagle 2 lost. However, it is nevertheless possible that Hirst’s spot painting survived and resides today on the Martian surface.

According to the ESA’s Director of Science, Professor David Southwood, it is unlikely that the lander burned up on descent or glanced off the Martian atmosphere and into deep space. In Southwood’s opinion, two other possibilities are more likely.

The first is that the parachutes and gas bags did not work (for a variety of reasons) to adequately slow the lander, causing Beagle 2 to crash into the Martian surface and break apart. Under this scenario, Hirst’s 3 x 3-inch aluminum plate spot painting could be sitting intact in a debris field scattered over several miles of Martian soil.

Another, equally plausible, possibility is that Beagle 2 landed intact but got entangled in the parachutes and airbags thereby preventing the top from opening. In this case, Hirst’s painting would definitely represent the first art to land on Mars.

Even if Hirst’s spot painting survives, it would have held the distinction of being the only art on Mars for just a few short days. That’s because on January 3, 2004, NASA successfully landed its own rover in Mars’ Gusev Crater.

Named Spirit, the rover contained artwork created by London-based Australian artist Stephen Little called Monochrome (for Mars). The artwork is contained in a DVD that includes the names of nearly 4 million enthusiasts who responded to NASA’s invitation to send their names to Mars. Little then engrafted red text reading “Monochrome (for Mars)” on the DVD.

“I could have sent a physical object, such as a painting,” said Little at the time, “but it had to be placed on a DVD, so I was limited by the space I had on it as well.”

Designed to last for three months, Spirit roved for more than six years. The rover sent its last message in March of 2010, and after nearly a year of trying to reestablish communications with the Spirit Mars rover, NASA finally decided to suspend efforts in 2011.

Of course, to recognize either Hirst or Little as the first artists on Mars requires an expanded view of what art is.

Some might contend that colors and pigments chosen and arranged to calibrate cameras and sensors should not qualify as real art, and that Little’s lettering is just labelling and not actual art. Or at least not art in the sense of the drawings that Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, David Novros, John Chamberlain and Forrest Myers included in the Moon Museum. Each of their contributions made a statement about the history of art or the state of their own body of work.

But if Yoko Ono and her colleagues have taught us anything since the 1960s about conceptual art, if Ben Patterson and his Fluxus contemporaries imparted any wisdom about happenings and performance art, then Hirst’s spot painting and Little’s Monochrome (for Mars) must be accepted as true works of art, and, therefore, Little and possibly Hirst must be recognized as the first and only artists with work represented on the red planet.

Support for WGCU’s arts & culture reporting comes from the Estate of Myra Janco Daniels, the Charles M. and Joan R. Taylor Foundation, and Naomi Bloom in loving memory of her husband, Ron Wallace.