Tropical Storm Debby didn’t look like trouble.

No hurricane-force winds. No mass evacuations. Just forecasts, quietly urgent, calling for historic rainfall.

Sarasota County officials weren’t alarmed. Days before landfall, the public works director — who two years earlier had called the county “one of the most flood-protected communities in the state, if not the nation” — went on vacation.

On Aug. 5, the rain came. Then the flooding. Then the reckoning.

In the Laurel Meadows neighborhood, foul-smelling water swept through dozens of homes, ruining appliances, rotting drywall and leaving owners collectively on the hook for millions of dollars in unexpected repairs.

In the Amish-Mennonite community of Pinecraft, nearby Phillippi Creek overflowed its sediment-choked channel until stormwater surged waist-high, pressing against door frames and windows. One man died after floodwaters from the creek swallowed his vehicle.

Near Celery Fields, floodwaters left a business park mold-infested and millions of dollars’ worth of machinery submerged and destroyed.

Sarasota County’s stormwater system is designed to steer floodwaters away from homes and businesses and safely to the coast. When Debby hit, the system proved dangerously unprepared when it mattered most — not because the system was overwhelmed, but because those in charge neglected to protect it, an investigation by Florida Trident and Suncoast Searchlight found.

To pinpoint what went wrong, reporters spent five months reviewing thousands of public records, including county emails, maintenance logs, financial records, consultant studies, aerial footage and meeting transcripts. They interviewed public officials, current and former county employees, stormwater engineers, environmental consultants and flood survivors.

Among the findings:

- Despite repeated warnings about sediment buildup in Phillippi Creek — the county’s largest watershed — county officials denied for years that maintaining it was their responsibility. In an interview with reporters in June, they finally conceded it was. The work, they said, had no dedicated funding — even with millions of dollars in stormwater reserves.

- The county’s stormwater division was unprepared and understaffed. Key positions sat vacant for months. Protocols meant to prevent flooding, like opening a gate at Celery Fields, went unfollowed, exacerbating the damage. Maintenance of stormwater infrastructure, including cleaning ditches and unclogging pipes, was backlogged for as long as eight months. The team operated in crisis mode — reacting to problems instead of preventing them.

- One of the worst failures unfolded just half a mile from the county’s own stormwater field services center. A berm, which functions like a levee, near the Laurel Meadows community had not been inspected in decades. After a portion of it gave way, floodwaters surged into homes, forcing evacuations and causing extensive damage.

- County leaders knew about glaring vulnerabilities in their stormwater system years earlier but did little to address them. A 2022 report by Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions warned the county it lacked the staff, resources and long-term planning to maintain existing infrastructure — let alone meet rising demand. It also outlined a series of proposed fixes. Many were delayed or ignored. Staff did not revisit the Wood report for more than two years and only after reporters asked questions about its status.

Now, one month into a new hurricane season, the stakes are only higher. The next storm could arrive at any moment — and many of the vulnerabilities exposed by Debby remain unresolved.

“There needs to be a change in the culture at stormwater,” said Steve Suau, a hydrologist and engineer who helped create Sarasota County’s stormwater utility in the late 1980s, during a community flooding meeting in April.

“Commissioners set policy and direction,” Suau said. “I think they understand the urgency.” Staff, on the other hand, he added, may not fully grasp what went wrong during last year’s flooding or recognize that reform is necessary. “In some ways, I’m not even sure they understand what happened.”

At the request of the county, Suau conducted an independent analysis of neighborhoods hit hardest by Tropical Storm Debby. He said he wasn’t surprised by the flooding. What concerned him was where — and how severely — it struck.

In several areas, including Laurel Meadows, Celery Fields and Pinecraft, Suau found, the damage exceeded what rainfall alone could explain.

More on the story

“What it turns out is every single one of those areas,” he said, “the reason they flooded worse was because of a lack of maintenance or operation of the system.”

There’s no question Debby delivered a rare and punishing storm to much of Southwest Florida and beyond. Across the region, storm drains, creeks and retention basins were overwhelmed, triggering widespread flooding from Manatee to Charlotte County. Even well-functioning systems would have been tested under that kind of pressure.

In a series of interviews with Florida Trident and Suncoast Searchlight, Sarasota County Public Works Director Spencer Anderson insisted that no system could withstand the up to 14 inches of rain Debby brought in a single day.

Sarasota County’s system, he noted, was designed for only 10 inches of rain in a 24-hour period — the highest standards in Florida.

Yet even as he defended his department, Anderson admitted crucial mistakes: neglecting routine inspections and forgetting to maintain the failed berm.

“If we would have known about that area and that it required maintenance, we would have done something better out there,” Anderson told reporters, referring to Laurel Meadows.

He denied that staffing shortages or disarray within the stormwater division impacted the outcome of the flooding, contending the county’s response was appropriate given real-time conditions.

Sarasota County Public Works Director Spencer Anderson, photographed here at the May 29 stormwater workshop, oversees the county’s stormwater division, in addition to other responsibilities.

“We haven’t flooded in 30 years,” Anderson said. “We must be doing it right.”

But a line from the 166-page Wood report suggested a different measure of success — one rooted not in past outcomes, but in preparation for the worst, assuming systems will face extreme events and must be ready for them.

“In this case,” the report noted, “success is the ability to protect property and lives as intended by the engineering of various stormwater management controls.”

Reporters also sent a list of detailed, written questions to County Administrator Jonathan Lewis, asking about, among other things, the stormwater vacancies, the lack of adherence to procedures and why many recommendations from the Wood report were not implemented.

Lewis redirected most of the questions to Anderson.

Anderson is now getting backup: On Wednesday, Lewis reassigned Assistant County Administrator Mark Cunningham to focus exclusively on stormwater efforts and “supplement the efforts of Spencer Anderson on a day-to-day basis” — a move that suggests concern about Anderson’s ability to manage the division alone.

After the floodwaters receded, public pressure mounted. Residents demanded answers.

In Laurel Meadows, that frustration has turned to potential litigation. In May, attorneys representing residents sent the county a legal notice, alleging negligence in the failure to maintain critical infrastructure near Palmer Boulevard and Lorraine Road.

Allison Cavallaro, whose home was among those damaged, said the goal isn’t litigation — it’s accountability.

“We want to be made whole,” she told reporters. “And we want them to fix this problem so it never happens again to any community.”

County sat on millions while neglecting Phillippi Creek

Sarasota County’s stormwater division is responsible for everything from clearing roadside ditches to inspecting underground pipes — work meant to keep rainwater moving and neighborhoods dry.

The system it oversees is sprawling and complicated: nearly a thousand canals and over 350 miles of pipes, governed by overlapping jurisdictions. Some are owned and maintained by the county. Others fall under homeowner associations or private property owners. State and federal regulations layer on further oversight.

While most counties in Florida manage stormwater in some form, Sarasota was the first to create a dedicated utility. Established in 1989, it centralized control and funded the work through an annual assessment charged to all property owners.

Each parcel pays a flat base fee, plus an additional charge tied to the amount of hard surface — like rooftops, driveways and paved areas — that keeps water from soaking into the ground. The median stormwater bill last year was $118.

Since 2008, the earliest year for which data is available, those assessments have generated nearly $339 million — enough to fund routine maintenance, infrastructure upgrades, and more recently, a growing surplus. A portion of the revenue is set aside each year in what Anderson has described as a “piggybank.”

By 2022, that piggybank held $10 million.

But county staff did not disclose the surplus that same year when they recommended — and secured — the first rate hike since 2009. Nor did they mention it earlier this year, when they sought a second, as-yet-unapproved hike.

Instead, staff told county commissioners the stormwater system was underfunded and overstretched, unable to keep pace with new development, tighter federal regulations and the rising threat of sea-level rise.

Within two years of the rate hike’s effect, the surplus had swelled to nearly $19 million.

“It is jaw-dropping that they had stormwater money set aside,” former county Commissioner Christine Robinson told reporters in May. “They could have used that money to catch up on stormwater maintenance before this hurricane season.”

Yet when droves of residents demanded to know why Phillippi Creek — the county’s largest watershed — hadn’t been dredged before it flooded homes during Tropical Storm Debby, county officials insisted there was no dedicated money to do so.

They not only had the money; they had known for years that sediment buildup in the creek was a problem. Residents had warned them. So had elected officials.

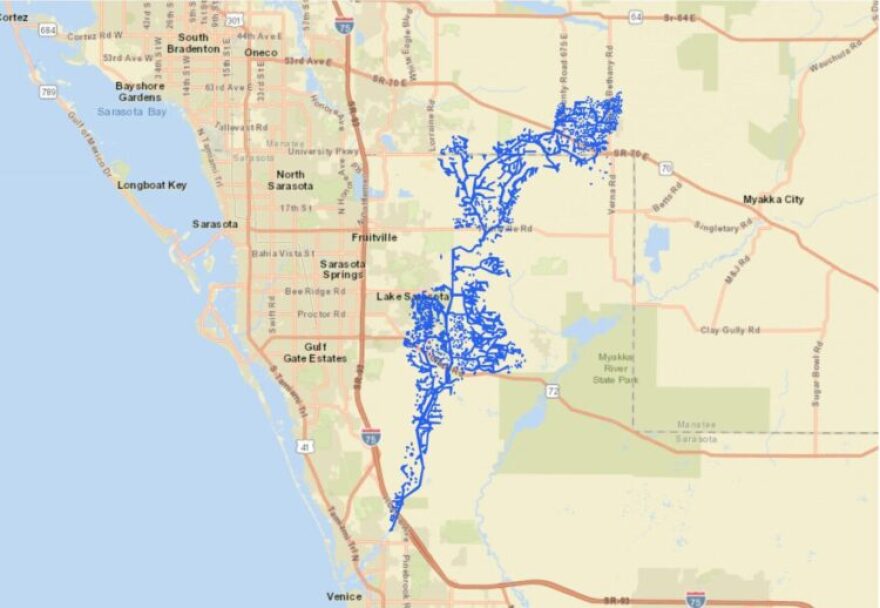

Phillippi Creek is the county’s single largest watershed that carries stormwater away from property, encompassing about 55 square miles. For years, residents living along its banks have urged the county to do something as sandbars grew.

In January 2023, county employee Joe Kraus forwarded his supervisors emails he had received from residents along the creek complaining that sediment clogged the channel. In his message, Kraus attached a federal grant application he drafted to dredge the waterway, in part, because sediment had reduced stormwater flow.

County staff never submitted the application, missing a key chance to secure funding long before Debby’s landfall.

More warnings followed. That July, Gary Gavin from Phillippi Landings requested the county perform maintenance dredging of Phillippi Creek, saying the creek has been “filling in making access either risky or impossible.”

Even Sarasota County Sheriff Kurt Hoffman weighed in, complaining in a letter to county staff that same month about sandbars slowing his deputies’ abilities to respond in emergency situations.

The answer was always the same: It wasn’t the county’s responsibility; there was no county-funded maintenance program; the public should consider private dredging and other resources.

But those responses didn’t match county policy. A 1999 maintenance plan explicitly calls for the county to remove sediment from public canals when it impairs stormwater function. And an ordinance amended in 2022 makes clear the county is obligated to maintain natural and artificial waterways that function as part of its stormwater system and authorized assessments to fund their maintenance.

Justin Bloom, an environmental attorney specializing in waterways, reviewed the 1999 maintenance plan and 2022 ordinance and concluded that canals, streams and rivers are a part of the system required to be maintained.

“The county undertook the responsibility, which was funded by taxpayers,” Bloom said, “to maintain a stormwater system for health and safety.”

By the time Debby hit, sediment-choked Phillippi Creek could no longer handle the surge of rain. Water rose fast, damaging homes, forcing evacuations and ultimately claiming a life.

In a final interview with reporters, Anderson acknowledged what the public had long believed.

“Phillippi Creek,” he said, “is clearly within the scope of the county’s responsibility.”

Stormwater team was reactive, backlogged and unsure of key protocols

Sarasota County’s stormwater division was in crisis well before Tropical Storm Debby arrived.

Tucked within the larger Public Works Department, the division is responsible for keeping floodwaters at bay — inspecting canals, mowing ditches, clearing clogged pipes and making sure the county’s vast drainage network works when it’s needed most.

But in the months before the storm, the team was running on fumes.

The division’s top manager had resigned in August 2023. Its field services supervisor, responsible for overseeing on-the-ground maintenance, had walked away in May 2024; that position remained unfilled for nearly a year. When reached for this story, both people declined to speak on the record.

For more than two years, one out of every five positions in the Stormwater Field Services unit sat vacant, according to an analysis of county records by Florida Trident and Suncoast Searchlight. The entire stormwater division saw at least 24 departures between July 2022 and April 2025.

One former stormwater employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid professional fallout, described the department as “disorganized and reactive.” The employee said “there was no accountability.”

The hardest positions to fill were the most essential. Crews who cleared overgrowth, unclogged pipes and kept water flowing were leaving faster than they could be replaced. A weekly vacancy report from March 2023 showed that stormwater field positions had been vacant for an average of nearly three years.

The churn wasn’t a mystery to Anderson.

In April 2023, the public works director emailed the county’s chief human resources officer a spreadsheet detailing why three dozen employees had left his department over the past year. More than half of the stormwater maintenance workers who quit cited low pay as a reason. Anderson flagged it plainly.

“Don’t know if you see these or not,” Anderson wrote to HR chief Chris Louria in his email, “but the pay issue with our blue collar team is a reoccurring (sic) theme.”

The county’s own exit surveys backed him up:

“This was a hard decision, but I can no longer afford to live on the wage I am making,” one outgoing employee wrote. “My goals of owning a home, getting married, and raising a family could not happen.”

Said another: “PayScale doesn’t move fast enough … We have had turnover, went through 8 co-workers and managers. Stability of the department is concerning.”

And a third: “I was offered a job with a construction job in Venice making $20,000 more a year. Loved working here, but I can not afford to.”

The departures had consequences. Routine stormwater maintenance fell behind. Backlogs of resident-initiated work orders stretched beyond six months, county officials admitted. Critical infrastructure — including canals, floodgates and berms — went uninspected or unmaintained, according to internal documents.

Even the county’s most critical public safety facility wasn’t spared.

The Emergency Operations Center — the hub for coordinating disaster response — went more than three years without a required stormwater recertification. So did Nathan Benderson Park, a public space reliant on functioning drainage systems. In both cases, Sarasota received warning letters from state regulators. One internal email blamed the lapses on “prior staffing failures to perform.”

An analysis of county records by Florida Trident and Suncoast Searchlight found the Stormwater Field Services unit had one in five positions unfilled during the past two years through April — a 20% vacancy rate.

“Vacancies are a normal part of the organizational process as employees move in, out, and up in the organization,” said county spokeswoman Genevieve Judge. “Human Resources uses a variety of recruitment strategies to fill vacancies in the county.”

Years earlier, the staffing problems were laid out in the Wood report in precise, technical terms.

Completed after years of analysis, the operational review warned that Sarasota County’s stormwater workforce was too small to meet existing needs — and unprepared for what lay ahead. Consultants recommended adding 26 full-time positions, citing a projected tripling of impaired waterways that would require long-term inspections, regulatory reporting and ongoing monitoring.

“These new systems will require inspections,” the report noted. “Current staffing levels make it challenging to ensure there are fully trained and experienced engineers” available for that work.

The message was clear: without more people, the system would fall behind.

By the time Tropical Storm Debby arrived, the county had yet to fill the serious gaps the report had identified.

Debby exposed Sarasota’s failure to follow its own flood plans

Cow Pen Slough is a 20-mile flood-control canal constructed mostly for agriculture that stretches from rural Manatee County south to Dona Bay in Nokomis. The canal divides two major watersheds: Phillippi Creek and Dona Bay.

Under agreements signed in the 1960s with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Sarasota County committed to maintain the infrastructure surrounding the canal — including a berm that functions as a levee along a section east of Rothenbach Park.

That obligation has been repeatedly ignored.

As early as 1979, the Southwest Florida Water Management District documented maintenance failures along the slough. Records show that pattern of neglect persisted for decades, through at least 2024.

One section of the berm, less than half a mile from the county’s own stormwater field services center, had gone untouched for years. It is now overgrown with Brazilian pepper, cabbage palms, tangled vines, fallen trees and thick brush — a wall of vegetation obscuring what’s supposed to be a critical flood barrier.

The berm is designed to keep Cow Pen Slough’s floodwaters from spilling west into lower-lying neighborhoods. But when that barrier fails, water rushes toward homes never built to withstand it — homes in neighborhoods like Laurel Meadows.

That’s exactly what happened during Debby.

Despite its proximity to county crews, the levee had not been inspected or maintained. Anderson acknowledged the lapse.

“I can absolutely tell you,” he told reporters, “that no one has done anything to that berm for probably 40 years.”

Pam Ferner lives at the end of Delft Road, in the last house before the canal bends behind Rothenbach Park. When floodwaters breached the earthen berm there during Debby, her home was among the first to be hit.

“It was coming in like a tidal wave,” she said. “We lost everything.”

But the signs of trouble had been there for years.

In 2017, Ferner had noticed something unusual: standing water on her property after heavy rain — something she said had never happened before. She called the county to report it, asking if someone could come take a look. No one came.

Then Hurricane Ian hit in 2022. Her home was surrounded by water. She called again. This time, the county sent someone out. But the employee told her everything looked fine.

Ferner now wonders if the berm had already been compromised.

“I kept contacting the county,” she said. “But they didn’t care.”

In the days after the storm, Anderson initially blamed clogged pipes for the Laurel Meadows’ flooding. He didn’t know about the breach — because no one had looked. He later asked Suau to conduct an independent review.

Suau quickly identified the canal as the source of the breach and directed staff to its location. The breach has since been repaired.

The forgotten berm wasn’t the only thing that worsened the flooding.

In 2014, the county paid the engineering firm Kimley-Horn to develop manuals detailing the operation of flood-control gates that discharge floodwaters.

The guidance was explicit: Open all internal gates at the Celery Fields early to drain it and free up flood-storage; keep the main gate leading to Phillippi Creek open during storms for controlled releases; and leave the Cow Pen Slough gates open for the entire storm season, June 1 through Oct. 31.

None of that happened during Debby. A critical gate on Cow Pen Slough remained closed until just days before the storm. Anderson later acknowledged to reporters that staff failed to follow the manual.

As Debby unleashed torrential rain, local water engineer Tony DeLoach grew alarmed. He was at Celery Fields — a nature preserve that doubles as a stormwater-management facility — documenting the rising water levels and emailing photos to Sarasota County stormwater staff.

DeLoach, who had worked on the site in the past, urged the county to open the main floodgate before the system was overwhelmed, according to emails obtained through a public record request.

The primary gate that drains water from Celery Fields, pictured here, was required to be open during the storm but instead remained closed.

By the next day, he was pleading again. “Water is flowing over the top of the gate. Does anyone monitor this??”

The county’s response came hours later: The gate would stay shut until the tide dropped since neighborhoods downstream were already flooding. But DeLoach warned that holding back water disrupted the system’s natural flow and could make conditions worse.

“The areas that are low have always been low,” he wrote. “The areas that never flooded now flood because of the flood gates and control. Is this better or worse?”

DeLoach declined to be interviewed for this story.

Tom Medel, a longtime stormwater employee pushed out in March 2023 after clashing with a supervisor, said that no one in the stormwater department took ownership of operating flood gates — despite his repeated calls to dedicate staff focused solely on flood prevention.

“There was no understanding,” he told reporters, “of why they did what they did.”

Anderson conceded to reporters that county staff did not follow the Celery Fields’ protocol. At one point, he said staff didn’t know the manual even existed. Later, he said decisions were made “on the ground” to avoid worsening the flooding downstream.

“At some point,” Anderson told reporters, “it was, you know, flood this person or flood that person.”

Then he reversed again, stating he wasn’t sure staff was even aware of the protocols, even though Jay Brown, a supervisor in stormwater field services, received them in an email from consultants five months before Debby, public records show. Brown was in charge of operating the Celery Field gates during Debby.

As floodwaters receded and public anger rose, soon-to-be county Commissioner Tom Knight watched closely. He hadn’t yet taken office when Tropical Storm Debby hit, but he said what he saw disturbed him.

To Knight, it reflected a deeper breakdown — one of accountability.

“As the former sheriff, my first thought was that there had been a failure of leadership,” Knight told reporters in May. “You have to recognize when there is a problem and be bold enough to address it, even if it’s uncomfortable. I felt that the county failed to lead with its response to the flooding.”

Suncoast Searchlight investigative data reporter Kara Newhouse and senior investigative reporter/deputy editor Josh Salman contributed to this report.

This story was produced by Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom of the Community News Collaborative serving Sarasota, Manatee, and DeSoto counties; and Florida Trident, a nonprofit newsroom of the Florida Center for Government Accountability. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org and floridatrident.org

About the Author: Michael Barfield focuses on the enforcement of open government laws. He serves as an investigative reporter for the Florida Trident and Director of Public Access at the Florida Center for Government Accountability. He regularly assists journalists across the country with collecting information and publishing news reports obtained from public records and other sources.