Mary LeGarde is a shapeshifter. Depending on the motif and emotion, she may work in Figurative Realism, Impressionism, Surrealism or Narrative Art.

For her painting in this year’s Naples Invitational, she combined Figurative Realism with Cubism. It was a necessity. Her muse was Pablo Picasso. The man pioneered the notion of artistic shapeshifting.

“We see him as this very tough, strong man,” said LeGarde. “That's our memory of him. And that’s how he saw himself.”

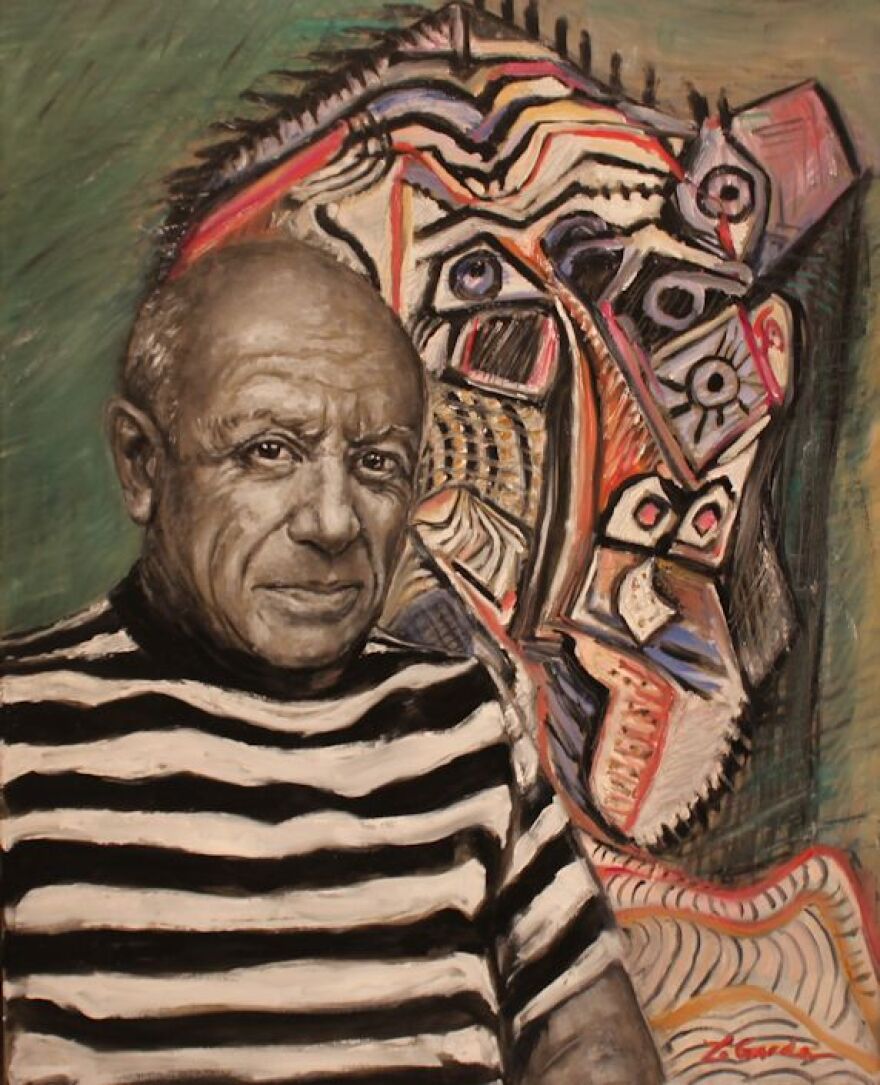

LeGarde calls her painting “Picasso’s Mirror.”

On the left, she’s rendered a realistic portrait of the artist in his iconic striped shirt, capturing the man as history remembers him: uncompromising, unabashed, full of machismo.

On the right is his Cubist self-portrait revealing the turmoil he experienced in his final days.

“It was done in crayon on paper, and it shows him falling apart sort of as his whole world is coming to pieces,” LeGarde noted.

Despite his public persona as a tough-as-nails creative and his late-in-life obsession with erotic subjects, Picasso was privately quite sentimental. That is what LeGarde brings out through the duality she conveys with “Picasso’s Mirror.”

“He had this gentle side of him that I don’t think really got expressed in his works so much as his machismo,” LeGarde said.

Naples Invitational is on view at the Naples Art Institute through Nov. 30.

MORE INFORMATION:

Florida Weekly describes her as the artist shapeshifter. An adjective that describes her younger self might be "precocious."

“I've been doing art my whole life,” said LeGarde at the opening of the 2025 Naples Invitational Biennial. “I started by destroying walls in my home with huge murals at age 4 with Cinderella scenes and horses and carriages.”

Her parents made her paint over her artwork.

LeGarde was unfazed.

“That didn't matter."

And undeterred.

"It happened again.”

The ersatz muralist persisted. At 15, she secured her first commission: a 20-foot mural that graced the walls of a local hospital.

“That painting ignited my passion for art,” she said.

In college, LeGarde studied art, sold paintings to pay for tuition and seemed inclined toward a career as a visual artist.

Life veered.

“Into a 20-year career as a successful trial lawyer,” LeGarde noted. In spite of a busy trial schedule, media appearance, marriage and motherhood, her zest for art never faded.

Life veered.

Her husband was diagnosed with AML leukemia.

“The hospital corridors became my studio,” LeGarde divulges on the home page of her art website, Mary LeGarde Studios. “I sketched him and his doctor, preserving their resilience in graphite.”

After he recovered, she re-evaluated her “life’s palette” and returned to painting.

One of LeGarde’s largescale paintings, “Aspens-Winter 1,” was selected as a finalist out of thousands of entries from around the world in the Art Renewal Center’s 13th International Realism Salon. Another canvas depicting a New England seas captain and pop star Rihanna was showcased on three episodes of NBC’s “Late Night with Seth Meyers.”

Her inclination to art navigated between Figurative Realism, Surrealism, Impressionism and Cubism, portraiture, landscapes and sculpture, which earned her the moniker of shapeshifter. It’s really just a steadfast refusal to be confined or pigeonholed.

“I blend tradition and innovation,” LeGarde explains on her website. “ Old Masters’ techniques infuse my oils and sculptures. Yet, I’m not a purist. Narrative art is my compass. I document today’s culture, dissect social issues and provoke thought.”

LeGarde exhibits widely. She’s had work in the Alliance for the Arts’ Pop-Up Museum 50 (2025), Method & Concept’s “Dia de Muertos” show (2024), Arts Bonita’s “Unbound: Exploring Surrealism in Art” (2024), Collier Museum at Government Center’s “Just Beachy” exhibition (2024), the 2023 Royal Tea Party auction benefiting the Ronald McDonald House for Charities of Southwest Florida, “Dark Art” and her solo “The Shapeshifting Artist” exhibition at the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center (2023) and United Arts Collier’s “Summer Art Exhibition” at Rookery Bay (2023).

She’s also been written up in Florida Weekly, The Naples Press, Southwest Florida Happenings Magazine and Opera Wire.

Picasso’s Gentle Side

Like LeGarde, Pablo Picasso refused to be confined to a single genre or mode of artistic expression. His art continued to evolve over the course of his life. He swiftly moved through artistic phases, co-founding Cubism with Georges Braque and Surrealism with Andre Breton. He pioneered the art of collage and assemblage, explored African and tribal art and pushed the boundaries of traditional disciplines ranging from painting to sculpture, ceramics and printmaking.

LeGarde says that beneath Pablo Picasso’s gruff exterior was a tender man. His ability to seamlessly transition between different styles and techniques showcased his versatility and artistic prowess.

While LeGarde’s painting focuses on his final days, as a young man he developed an especially close relationship with his art representative and dealer, Paul Rosenberg. The two men first met in Biarritz, where Picasso was on his honeymoon with his bride, Russian dancer Olga Koklova.

Not long after they met, Rosenberg persuaded the fledgling artist to move across the street from him. There, the Picassos and Rosenbergs became close friends, with Picasso often walking across the street to sketch the Rosenbergs’ little girl, Micheline.

He became quite fond of the child, who called him “Casso,” doing pencil sketches of her in a sailor suit, dressed in white in front of a bench and holding a stuffed rabbit.

His painting “Portrait of Madame Paul Rosenberg and Her Daughter” is a testament to the couples’ emerging friendship and Picasso’s infatuation with the Rosenbergs’ chubby baby.

Always prolific, Picasso was reputed to have stood in the window of his apartment holding up his latest painting to give first peek to his friend and little Micheline. In time, Picasso would refer to Rosenberg as “Rosi,” who in turn called him “Pic.”

Their personal and business relationship became extraordinarily complex following Hitler’s ascendancy to power in 1933. Not only was Rosenberg Jewish, but his vast collection also became the target of Nazi greed, particularly on the part of Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, an avid art collector.

Through guile and his considerable connections, Rosenberg was able to spirit a vast number of Picasso’s works out of Europe for a large retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago. That was a good thing, because the Nazis would eventually seize 300 works from Rosenberg’s personal and professional inventory, including a number of Picassos that Rosenberg held on account.

In many ways, these and his other experiences in war-torn Europe during two world wars hardened Picasso, forcing him to bury his emotions and sentimentality under a hardened façade. Although gregarious and affable by nature, he became increasingly reclusive in his later years and estranged from three of his children, Maya (his daughter with his longtime mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter), and Claude and Paloma (his children by Françoise Gilot).

It was not that he’d grown weary of people.

“Work is what commands my schedule,” Picasso told a friend.

Still, the night before he died, Picasso and his fourth wife, Jacqueline, entertained friends for dinner at their hilltop retreat on the French Riviera. As was his way, he got up abruptly at 11:30 saying, “And now I must go back to work.”

Work he did, until 3 a.m.

Work was Picasso’s refuge. Neither war nor marital strife or surgeries or failing health could diminish his artistic output.

While that Cubist self-portrait on the wall behind the artist in “Picasso’s Mirror” might depict a man who was valiantly trying to keep it together in the waning years of life, his creativity and artistic expression remained the glue that kept everything in place.

In doing her research for “Picasso’s Mirror,” LeGarde discovered something else about the artist.

“He wanted the world to express their artistic values, whether it is done through the applied arts or the visual arts or through anything you do in life,” said LeGarde. “That was the point that he left with us, his story, that he sort of lets us continue in our lives.”

Support for WGCU’s arts & culture reporting comes from the Estate of Myra Janco Daniels, the Charles M. and Joan R. Taylor Foundation, and Naomi Bloom in loving memory of her husband, Ron Wallace.