The Florida black bear, designated as a threatened species by the state in the 1970s, will have its rebounding numbers culled by 187 of the animals in December.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission voted unanimously Wednesday in favor of a statewide black bear hunt during a meeting in Havana, a town of about 1,500 residents near the Georgia state line north of Tallahassee.

There are an estimated 4,000 black bears in Florida, one of the few states with sizable populations that do not have a bear hunting season. Several pro-hunt speakers noted that bears are now much more commonly seen in many areas than in the past, leading to interactions with humans that provoke fear and concern.

“We make decisions based on science,” Rodney Barreto, FWC's chair, said.

Opponents called the hunt cruel, unnecessary, and an excuse for hunters to bag a trophy animal when the real issue is the encroaching human population in bear habitat, as Florida continues to grow. There was strong opposition to using dogs to corral the bears and to target the animals in baited locations.

Ragan Whitlock, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, said hunting could do real damage to Florida’s recovering population of black bears.

“I’m deeply troubled that the commissioners disregarded the science and approved an annual Florida black bear hunt,” said Whitlock. “This irresponsible decision contradicts the commission's own black bear management plan, undermines decades of great work by its black bear team and threatens recovery of the species. The commissioners’ vote was based on obsolete data and goes against science, against the recommendations of its staff and against what Floridians want.”

Bobbie Lee Davenport, who organized two protests in Naples in recent months against the hunt, said it defines animal abuse.

"It's a sad day in Florida. We've been betrayed by the agency that is supposed to be here to protect wildlife," she said. "You know I don't know where we are going to go from here because the last hunt in 2015 was criticized internationally. This is a crime against nature."

Regulated hunts such as this have long been a routine tool used in American wildlife management to control overabundant animal populations. The practice has a well-established history and is grounded in scientific principles of wildlife management.

The hunt is not intended to eradicate bears or drastically reduce their numbers — it’s a conservative, targeted effort to thin what the state claims is an animal approaching overpopulation, which could otherwise lead to resource shortages, increased human-wildlife conflicts, and ecological imbalances.

Animal rights advocates disagree. They firmly believe the hunt could be avoided by using non-lethal tools, such as ads to remind people to secure trash cans to avoid attracting bears near people.

Opponents have also said Florida's black bear hunt is not only unnecessary but cruel, because of the trained dogs that corner the bears for hunters to shoot, and the "bait stations" filled with food for bears, which are shot by hunters lying in wait.

Florida's 2015 black bear hunt was initiated with good intentions, but ended in chaos, with animal rights activists livid.

Conservation measures — including a ban on bear hunting — helped Florida's black bear population increase from a few hundred in the 1970s to more than 4,000 by 2015.

Like now, state wildlife officials then decided to thin the bear's booming population, worried about conflicts between bears and people, by allowing hunters to kill 320 of the animals.

Yet more than 3,700 hunting permits were sold. That meant nearly as many hunters looking to shoot and kill black bears as there were black bears.

Things went sideways right away.

Florida’s bears had not faced hunters for decades, so their fear of humans had waned to a degree. It was a free-for-all.

The hunt was split into zones, each with its own bear quota that officials trusted hunters would follow. In Florida's Panhandle, hunters blew past their limit of 40 bears and killed 112. Central Florida hunters also exceeded their quota.

Stories emerged of mother bears shot while nursing cubs. Critics said more than 100 cubs were orphaned. Hunters killed bears smaller than the legal limit.

Wildlife officials called off the planned weeklong hunt of 320 bears after two days, when 304 had already been killed.

Controversy exploded. Animal rights groups condemned it as “state-sanctioned slaughter.”

Faced with public anger and mounting mistakes, wildlife managers ended the hunt early. No black bear hunts have been held since then. Officials have floated possible future hunts, but for now, Florida’s bears—mother and cub alike—remain protected.

The new style of hunt caps participation at 187 hunters, each of whom will have won a chance to pay between $100 and $300 for a permit to kill one bear. Better oversight will avoid the killing of any females with cubs, according to the FWC staff.

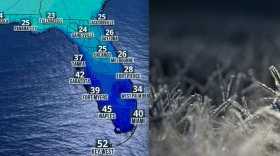

Bears will be allowed to be hunted only in areas of Florida where the FWC believes the animal’s population is strong enough to withstand the losses, such as the 55 bears that will be allowed to be hunted in the Big Cypress region in Southwest Florida.

Other places with bear limits include 68 bears in the Apalachicola region west of Tallahassee, 46 in areas west of Jacksonville, and 18 in an area north of Orlando.

There has been only one documented fatal black bear attack in Florida. That incident happened this past May and involved the mauling of 89-year-old Robert Markel and his daughter’s dog in a rural part of Collier County.

Environmental reporting for WGCU is funded in part by Volo Foundation, a nonprofit with a mission to accelerate change and global impact by supporting science-based climate solutions, enhancing education, and improving health.

Sign up for WGCU's monthly environmental newsletter, the Green Flash, today. WGCU is your trusted source for news and information in Southwest Florida.

We are a nonprofit public service, and your support is more critical than ever. Keep public media strong and donate now. Thank you. WGCU is your trusted source for news and information in Southwest Florida. We are a nonprofit public service, and your support is more critical than ever. Keep public media strong and donate now. Thank you.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.