Feb. 20 is the most important date in the history of Fort Myers.

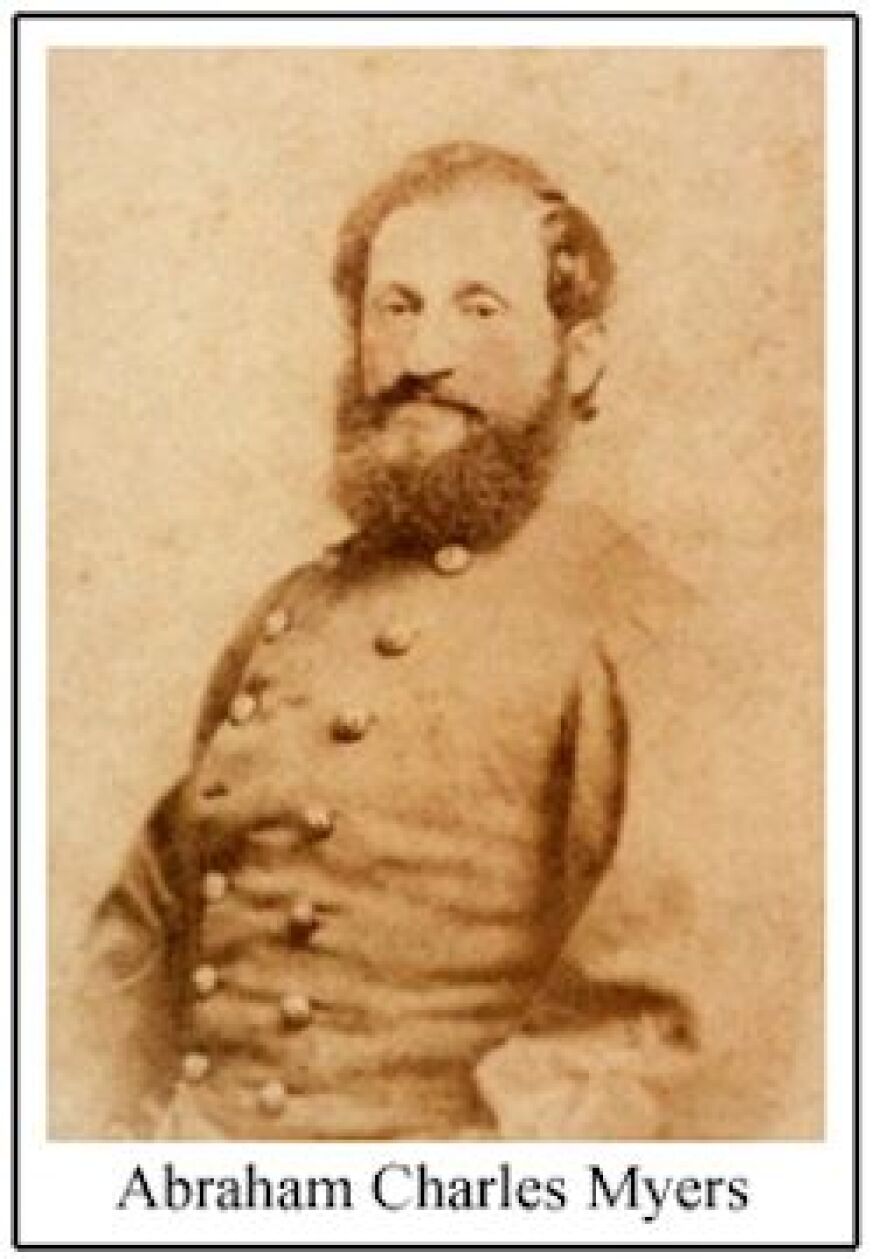

On this day in 1850, two companies of artillery landed on the banks of the Caloosahatchee River near present-day Florida Repertory Theatre and began building a frontier outpost they named Fort Myers in honor of General David Emmanuel Twigg’s soon-to-be son-in-law, Lt. Colonel Abraham C. Myers, who was chief quartermaster for all of Florida.

On this day in 1865, Union soldiers led by two companies of the United States Colored Troops 2nd Regiment repelled an attack by the Confederate Cow Cavalry, who were under orders to burn the fort to the ground. Had that happened, it’s likely that Manuel Gonzalez would have settled elsewhere instead of Fort Myers when he arrived on Feb. 21, 1866.

And on this day in 1904, Fort Myers was finally connected to the rest of the country by rail service. Prior to the arrival of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, the only way in or out of Fort Myers was by boat, which was impractical for travelers and for shipping perishable products such as citrus to markets in Tampa, Miami and beyond.

MORE INFORMATION:

Construction of Fort Myers began on Feb. 20, 1850

On Feb. 20, 1850, a brevet major by the name of I.C. Ridgely arrived on the shores of present-day Fort Myers with two companies of artillery under orders to establish a fort to be named Myers.

It does not appear that Colonel Abraham C. Myers or his wife, Marion, ever visited his namesake, but all building plans had to be approved by the colonel, who was also in charge of allocating the funds necessary to purchase the materials to be used at the fort. Myers spent so much money on his namesake that in 1856, the War Department ordered an investigation.

The fort was massive. Although accounts vary, it appears that the stockade ran from just east of present-day Broadway on the west to just east of Royal Palm on the east and Main on the south to the riverbank on the north, which at the time meandered along what is present-day Bay Street. It consisted of a number of officers’ quarters (running along the area now occupied by the Arcade Theater and the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center), barracks, administration offices, a 2½-story hospital with plastered rooms, warehouses for the storage of munitions and general supplies, a guard house, blacksmith’s and carpenter’s shops, a kitchen, bakery, laundry, stables for horses and mules, a gardener’s shack, and even a bowling alley and bathing pier and pavilion.

It also boasted a pier nearly 750 feet long that had a wide dock and rails that enabled the soldiers to tram in supplies. The hewn pine buildings were sided and topped by cedar shingles shipped in from Pensacola and Apalachicola, together with doors, windows and flooring. Inside the circumscribing stockade were parade grounds, a carefully tended velvety lawn, shell walks, lush palms, citrus trees and rock-rimmed riverbanks, as well as two immense vegetable gardens outside the southern stockade where City Hall stands today.

The fort was built in two stages. Makeshift buildings went up between 1850 and 1852. During that span, the Army tried to induce Seminole Chief Billy Bowlegs to self-deport with his people to Indian territory in Oklahoma. When it became clear that that they’d have to use force to deport Bowlegs and the Seminoles, the stockade and buildings were reinforced and expanded. Everything was apparently in good stead when future “Father of Fort Myers,” Francis Asbury Hendry, visited the fort for the first time.

So impressed was Hendry, that he waxed eloquently about what he had seen.

“The fort presented a beautiful appearance,” Hendry wrote. “The grounds were tastefully laid out with shell walks and dress parade grounds and beautifully adorned with many kinds of palms. The velvety lawn was carefully tended. Special care was given to the rock-rimmed riverbanks. I beheld the finest vegetable garden I ever saw. It was the property of the garrison, and the vegetables were supplied to the different companies in any quantities needed. Near the garden there was a grove of small orange trees. The long lines of uniformed soldiers with white gloves and burnished guns, and the officers with their golden epaulettes and shining side arms, were grand and magnificent to behold.”

Hendry went on to write that he had never seen a more comfortable and happy set of men. But ceramic tile muralist Barbara Jo Revelle does not want anyone today to glean a false impression from accounts like these.

“In this mural,” she wrote about the 20-foot tall by 100-foot-wide artwork located in the Banyan Hotel courtyard off First Street, “I wanted to represent some of the lesser known (and perhaps even suppressed) chapters in Fort Myers history, some of the events associated with the actual Fort Myers fort.”

The fort was an affront to the Seminoles, being constructed in the middle of land promised to them at the end of both the First and Second Seminole Wars. It was built for the sole and specific purpose of ousting the Indians from their lands at the behest of wealthy plantation owners in the northern part of the state who wanted to drain the Everglades so that they could put 100,000 enslaved people to work growing sugar cane and rice in the fertile muck left behind. And in 1856, soldiers from the fort provoked a war when they destroyed Chief Bowlegs' gardens and roughed him up when he arrived on the scene and demanded compensation for the crops they’d trampled underfoot.

Still, without the fort, there’d likely be no Fort Myers as we know it today. So despite this ignominious taint, Feb. 20, 1850, remains a key date in the annals of Fort Myers history.

Union soldiers won Battle of Fort Myers on this day in 1865

The Battle of Fort Myers was fought on Feb. 20, 1865. Many are surprised to learn that Fort Myers was a Union stronghold during the Civil War, and that the attack was initiated by a home-grown battalion of Confederates which was formed to oppose forays by soldiers from the fort into cattle country from Punta Gorda north to Tampa.

Prior to 1864, the ranchers had been supplying beef to Confederate troops, as well as providing steers to blockade runners who were trading them in Cuba for much-needed provisions. But toward the end of January in 1864, the Union soldiers garrisoned at the fort began confiscating the ranchers’ cattle. In fact, they were so successful that by January 1865, they’d appropriated more than 4,500 head, the majority of which they drove to Punta Rassa, where they were loaded on ships and taken to Key West to feed the sailors manning the flotilla that was blockading the coast of Florida.

As if the confiscation of their cattle was not bad enough, two companies of the Union soldiers stationed at Fort Myers were Black. Not former slaves, but free men mostly from Maryland. And they discharged their duties with a fervor the Confederate sympathizers especially loathed. The Confederate Army couldn’t spare any soldiers to attack the fort, so at the direction of John McKay, Sr., chief commissary for the Fifth District of Florida, the ranchers formed a home-grown battalion to protect their slaves and what was left of their cattle. They were officially named the Florida Special Calvary, 1st Battalion, but everybody referred to them simply as the Cow Calvary, and they headquartered in Fort Meade near Tampa under the command of Colonel Charles J. Munnerlyn.

In January 1865, Munnerlyn sent Major William Footman and three companies of the Cow Calvary to destroy Fort Myers. Included in that contingent was Capt. F. A. Hendry, who had raised and was commanding a company of 131 men.

Footman set out with 275 men on the two-week 200-mile march to Fort Thomson near present day LaBelle. Some accounts claim that his contingent had swelled to 500 men as angry local farmers, fishermen and other partisans rushed to join the fray. However, others contend that Footman would not have had provisions to sustain a larger force, although a handful of partisans may very well have joined in.

After resting a day, they marched down the Caloosahatchee River to mount a surprise attack on the fort the following morning. Unfortunately, the overeager vanguard of Footman’s force ambushed a handful of the Black Union soldiers they discovered on picket duty, thereby alerting the Union forces inside the fort to prepare themselves for battle.

Seeing that he’d lost the advantage of surprise, Footman ordered his men to fire a warning shot from their sole piece of artillery, a bronze 12-pounder. Then he sent a messenger under cover of a white flag to demand the fort’s surrender. Captain James Doyle gave a terse response. Via the messenger, he told Footman: “Your demand for an unconditional surrender has been received. I respectfully decline; I have force enough to maintain my position and will fight you to the last.”

Led by the Black soldiers in the fort, the Union contingent repelled the attack and thereby saved the fort from being burned to the ground. While people living in Tampa and Cedar Key in need of wood to rebuild their homes cannibalized the fort in the months following the fort’s abandonment in June of 1865, enough remained to entice Fort Myers’ first settlers, Manuel A. Gonzalez, his 5-year-old son, his brother-in-law John Weatherford and close family friend Joseph Vivas to remain when they sailed up the river in February 1866 to make their home in the remnants of the old fort. Had the Cow Cavalry prevailed and destroyed the fort, it is entirely possible that Gonzalez, Weatherford and Vivas might have returned to Key West or established their settlement elsewhere, precluding the town from evolving into the cow town that it did.

The Battle of Fort Myers is the subject of two public artworks located in the downtown Fort Myers River District, the memorial Clayton by late Fort Myers sculptor Don J. Wilkins, which is located in Centennial Park, and the 20-by-100 foot sepia-tone ceramic tile Barbara Jo Revelle mural, “Fort Myers: An Alternative History,” which is located in the courtyard shared by the federal courthouse, Banyan Hotel and Starbucks off First and Broadway. Fort Myers newest public artwork, Marks & Brands, pays homage to the role played by the cattlemen who migrated to this area and built the fledgling town of Fort Myers in the years following the Civil War’s end.

On this day in 1904, the railroad finally came to town

On this day in 1904, Fort Myers entered the modern era when the railroad finally came to town. The last rail went down at 11 a.m. at Monroe Street where the railroad dock was being built.

“The large town flag was secured, and Engine No. 499 was draped in the national colors,” The Fort Myers Press reported. “Then the young ladies hustled about and secured large bunches of flowers and soon had the headlight, flag standards and pilot of the engine bedecked with flowers. Mrs. Frierson and Mrs. James E. Hendry sent an immense and beautiful bouquet to F.L. Long and the other railroad men.”

Fort Myers’ female pioneer Julia Isabel Frierson Hendry drove the final spike into the freshly laid railroad ties.

“Then as the last spike was made ready, Mrs. James E. Hendry was escorted to the track, given a sledgehammer, and drove home the last spike that held the rails that connected Fort Myers with the great railroad system of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the entire country,” the Press went on. “Then the crowd cheered, the cannon boomed, whistles blew and bells rang. Mrs. T.J. Evans had prepared a treat for the railroad men consisting of sandwiches, sausages, cookies, homemade candies, etc. while a box of 500 oranges, cigars and cheroots was furnished by the businessmen.”

The town’s giddiness over getting the railroad might seem silly today, but it was completely understandable once you know that the town had unsuccessfully tried to induce the railroad’s previous owner, Henry B. Plant, for nearly two decades to bring rail service to Fort Myers. Plant had spurned their entreaties, building his rail line to Punta Gorda instead of Fort Myers. It was only after Plant’s death on June 28, 1899, and the subsequent sale of his holdings to Atlantic Coast Line Railroad on April 4, 1902 that Walter Langford was finally able to persuade Coast Line to bring their lines to Fort Myers.

It is also sobering to know that at the time, there were no bridges spanning the Caloosahatchee River or passable roads leading into or out of town. Thus, the only way for tourists to visit Fort Myers or for residents to travel elsewhere was by steamer and schooner to ports in Charlotte Harbor, Tampa and Key West, with connecting rail service to destinations beyond – a long, arduous and expensive ordeal.

The arrival of the railroad in Fort Myers is captured in the 20-by-100-foot-long sepia-toned ceramic tile mural that artist Barbara Jo Revelle installed in the courtyard shared by the federal courthouse and Hotel Indigo in downtown Fort Myers.

Two other events took place on February 20

Two other events took place on Feb. 20 that impacted local history.

The first involves Ponce de Leon.

On Feb. 20, 1521, Juan Ponce de Leon set sail from Puerto Rico for Southwest Florida with two ships, 200 soldiers, an indeterminate number of settlers and priests, 50 horses, a herd of swine and a boatload of agricultural implements. Although Ponce de Leon was convinced that he could successfully establish a Spanish farming settlement here, the trip ended in disaster for the ersatz conqueror, who wanted to explore the interior in hopes of finding the fabled fountain of youth.

No one knows for sure where he landed. It could have been Sanibel, Pine Island, Punta Rassa or somewhere along the Caloosahatchee River or even the Peace River.

“The landing place selected, no time was lost in bringing goods and men ashore, small boats shuttling back and forth between the ships and land,” wrote historian Karl Grismer in “The Story of Fort Myers.” “Then, suddenly, there came a rain of arrows from the shadows of the forest. And spears thrown with deadly accuracy. Many of the spears and arrows found their mark and Spaniards fell. Their blood spilled upon the sand.”

Other accounts maintain that the attack came when Ponce led a party into the interior in search of water.

In either case, one of those felled by the Calusas’ poison arrows was Ponce de Leon himself. Even though he was wearing body armor, a Manchineel-tipped arrow buried itself deep in one thigh. Writhing in pain, he staggered into a boat and was taken back to his ship. When the last of the survivors came on board, the anchors were lifted, and the ships hightailed it to Havana.

The Manchineel is one of the most poisonous trees in the world. The sap not only prevented the wound from healing, but also induced infection and finally sepsis. He explorer succumbed that July.

“Instead of finding the Fountain of Youth, he found death,” concluded Grismer.

And who knows? Fort Myers could very well have been the site of the historic battle that claimed the great conquistador’s life. After all, everyone else who sailed up the river looking for a place to establish a fort or settlement – from Capt. H. McKavitt to Major Ridgely to Manuel A. Gonzalez and his party – landed on the inviting hammock with towering pines and moss-covered oaks that is now downtown Fort Myers. So why not Juan Ponce de Leon?

According to the historic marker outside the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center, the site once served as home to a settlement of Calusa Indians. The clash between the native Calusa and Spanish was explored by the art, lectures and related presentations of “ArtCalusa: Reflections on Representation,” a November 2014 exhibition co-curated by archaeologist Theresa Schober and art consultant Barbara Anderson Hill. It was figured prominently in the discussions at “The Calusa in Colonial Florida,” a five-speaker presentation hosted by The Friends of Koreshan State Historic Site to commemorate the 450th anniversary of the first meeting between St. Augustine founder and Spanish naval commander Pedro Menendez de Aviles and the great Calusa chief, Carlos. Moderated by local archaeologist and former Mound House director Theresa Schober, the panel consisted of herself and Dr. Jerald Milanich, Dr. Kathleen Degan, Dr. J. Michael Francis and Dr. John E. Worth.

Now fast forward to 1915.

On Feb. 20, 1915, Dixie Highway advocates celebrated completion of Caloosahatchee Bridge at Olga. Completing a bridge across the Caloosahatchee River at Olga may not seem like such a big deal today, but 100 years ago today the Dixie Highway advocates hailed the span as a major breakthrough in connecting Fort Myers to the outside world.

With the bridge in place, the county then embarked upon a road building project that entailed constructing a 9-foot-wide asphalt surface going upriver, passing through Alva and LaBelle, and continuing eastward along the southern shore of Lake Okeechobee to the Palm Beach County line.

“Many influential citizens of Lee County lived up the river in sections which would be benefitted by the Dixie Highway and, naturally, they were staunch advocates of that route,” noted historian Karl Grismer in “The Story of Fort Myers.” “So were many prominent citizens of Fort Myers who owned large tracts in the upriver region.”

One prominent local citizen who was not a fan of the project was Capt. Fred J. Menge.

The captain came to the area in 1881 to help Hamilton Disston drain the Everglades. When Disston suspended operations in 1888, Menge purchased two small boats from Disston and formed the Menge Brothers Steamboat Line with this brother, Conrad. Over the years, the brothers brought bigger and better boats, and the line played an important role in the development of the upriver sections of Lee County.

But Dixie Highway dealt the Menge Brothers Steamboat Line a fatal blow. They were forced to close, ending a glamorous period in Fort Myers’ early history.

Ironically, the new highway did nothing to connect Fort Myers with points north of the river as the Dixie Highway remained nothing but a dream north of Olga, with opponents to the project ridiculing the new span as the “bridge to nowhere.”

It would be another five years before a crude marl road would be constructed, but its completion was totally overshadowed two years later when Tamiami Trial officially opened with the completion of a wooden bridge between Fort Myers and North Fort Myers on March 12, 1924.

WGCU is your trusted source for news and information in Southwest Florida. We are a nonprofit public service, and your support is more critical than ever. Keep public media strong and donate now. Thank you.

Sponsored in part by the State of Florida through the Division of Arts & Culture.