When it comes to jazz, Music Director Andrew Kurtz has his favorites.

“The February concert, Feb.19th, the Jazz Trio, they're doing a tribute to Count Basie and Duke Ellington,” said Kurtz. “For me personally, those are two of my favorite jazz artists.”

Both Basie and Ellington played at McCollum Hall, which was a venue on the Chitlin Circuit between 1938 and the 1960s. The Jazz Trio will celebrate the timeless swing, elegance, and innovation of the two legendary bandleaders who shaped the sound of American music.

For this performance, there are no guest artists. It’s Paul Gavin, Zach Bartholomew and Brandon Robertson unfiltered.

“There's a natural communication between all three of them because they've done so much collaboration at this point that to hear that and to hear the way they naturally give and take as well as genuine, musical courtesy, knowing when to pass to each other, it just comes out,” Kurtz observed. “So, that's going to be a great show.”

“A Tribute to Count Basie & Duke Ellington” is at 7 p.m. on Thursday, Feb. 19 in the Music & Arts Community Center off Daniels Parkway. Information on tickets can be found, here.

MORE INFORMATION:

Kurtz felt it important to point out that he and Paul Gavin did not schedule this show because February is Black History Month.

“I don't need a holiday to program music by Black artists,” said Kurtz. “I want to bring in the best possible world-class artists all year round and we may make a nod here and there to recognize people who are historically underrepresented, but I try and incorporate that actually year-round, not just say it has to be at this time of the year.”

While Kurtz did not include “A Tribute to Count Basie & Duke Ellington” in the trio’s season to commemorate Black History Month, their inclusion does comport with America 250. So keep reading for a trip back in time to McCollum Hall and some of the musical dignitaries who played there during the infancy of jazz and the Harlem Renaissance.

McCollum Hall’s place on the Chitlin Circuit

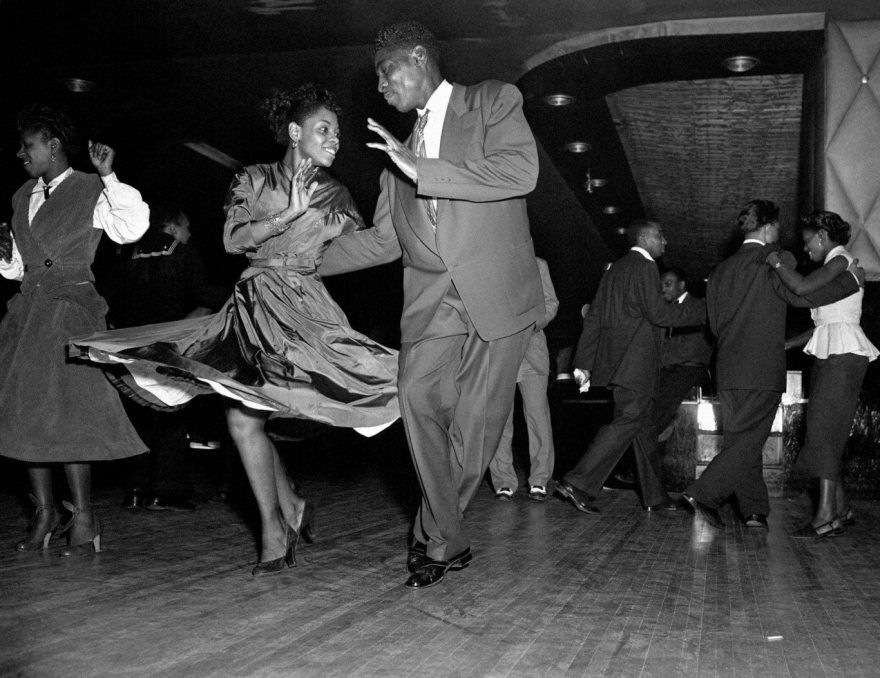

The “Chitlin’ Circuit” was a network of tight, crowded nightclubs, dance halls, juke joints and theaters in African American neighborhoods in the Midwest and Southeast that hosted some of the best talent in American music history.

With its year-round good weather, Florida had three dozen Chitlin’ Circuit locations, including the palatial Two Spot in Jacksonville, the Cotton Club in Gainesville (which became the Blue Note in the 1950s) and Club Eaton some six miles north of Orlando. Including Harlem Square, Miami had 10 Chitlin’ Circuit performance venues and African-American entertainers made a continual pilgrimage between Miami, St. Pete, Orlando and Jacksonville in their hardscrabble effort to make a living and pay their bills.

Following its completion in 1939, McCollum Hall became a desirable midway between St. Petersburg’s Manhattan Casino and the Harlem Square Club in Miami. Visiting musicians typically performed in Fort Myers on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, between weekend gigs in Tampa and Miami.

The Chitlin’ Circuit was born of necessity. This was the era of Segregation, and entertainers of color were denied access to white establishments and languished in an industry controlled by white theater owners and booking agents. So, they performed in clubs, juke joints and theaters in African-American neighborhoods.

The circuit was an economic godsend for the Florida towns and African American neighborhoods like Dunbar that played host to Chitlin’ Circuit entertainers. In most neighborhoods, the venues were situated on "the stroll," a bustling strip where one could find markets, BBQ pit stops and beer joints lining the road.

“These blocks were often monopolized by a local entrepreneur who dabbled in real estate, gambling, liquor and entertainment,” writes Matthew Leimkuehler in a February 8, 2021, article in the Nashville Tennessean titled “The roaring night that shaped American music.” “[Preston] Lauterbach [in his 2012 book ['The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll'] referred to these metropolitan ‘kingpins’ as the ‘true backbone of the Chitlin' Circuit.’"

McCollum Hall’s owner, Buck McCollum, was just such a figure.

Because the entertainers and patrons were expected to look sharp at the shows, “Black-owned barbershops and beauty salons, clothing and shoe stores all did a booming business, [as] did the liquor store,” notes Rev. Billy C. Wirtz in his May 9, 2022, Florida Humanities article, “Traveling Down the Chitlin’ Circuit.” So, it was no accident that Buck McCollum opened these very establishments on the ground floor of his emporium.

Besides the entertainers and their entourages, McCollum Hall and its first-floor businesses attracted Negro League baseball players during season as well as the pugilists who fought in the prize fights that Buck McCollum frequently staged in the event center.

During World War II, McCollum Hall functioned as the U.S.O. for Black servicemen stationed at the nearby Buckingham and Page Army air fields. (The detached upper floor of the Pleasure Pier, known now as the Hall of 50 States, served as the U.S.O. for white soldiers. But while Black servicemen were denied access to the white U.S.O. hall, white soldiers often frequented McCollum Hall.)

The Chitlin’ Circuit took its name from cast-off pork parts – hog intestines that were boiled and then fried. But there was nothing cast-off about the music that patrons heard on Chitlin’ Circuit stops.

Chitlin’ Circuit venues like McCollum Hall became the incubators of some of this country’s greatest blues, jazz and rock-and-roll musicians. Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, Lionel Hampton, Otis Redding, Lucky Milliner and Duke Ellington and his orchestra were among the Black musicians who performed at McCollum Hall. James Brown, Little Richard, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Muddy Waters, Fats Domino, Marvin Gaye, Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin, Ella Fitzgerald, Tina Turner, Sam Cooke, the Isley Brothers and even Jimi Hendrix all got their start, honed their performance skills and developed their unique sounds and flamboyant personas on the Chitlin’ Circuit.

And as the rhythm sections of the bands that toured with these and other musicians began insinuating gospel backbeat into their performances, the circuit eventually, inexorably, gave birth to a brand-new genre: soul.

While the Circuit’s heyday extended from the 1930s through the ‘60s, it traced its roots to vaudeville, a popular form of blue-collar entertainment that encompassed stand-up comedy, dance routines, minstrel shows, musical acts and staged plays. Fort Myers’ early movie houses, the Grand and the Court Theatres, both intermittently booked vaudeville acts to supplement the revenue they derived from films and entice patrons to the movies they normally screened. Harvie Heitman’s Arcade Theatre actually began its existence as a vaudeville venue, producing magic acts, local talent nights and plays, before it re-organized itself into a pure movie house on February 5, 1917.

“The Chitlin’ Circuit was African-Americans making something beautiful out of something ugly, whether it’s making cuisine out of hog intestines or making world-class entertainment despite being excluded from all of the world-class venues, all of the fancy white clubs and all the first-rate white theaters,” writes Preston Lauderbach in his 2012 book “The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll.” “The pay was low (‘Sometimes you play for the chitlins, that’s what you would get,’ Bobby Rush, the Grammy-winning self-described King of the Chitlin’ Circuit said in an interview one time), the schedule grueling (entertainers often performed two or more shows a night, 51 weekends a year, with James Brown once playing 37 shows in 11 days), the travel fraught with danger, but with verve and tenacity, musicians could eke out a living while creating a name and following for their music.” For those who made it, the Chitlin’ Circuit was a badge of honor, a proverbial rite of passage.

While most Chitlin’ Circuit venues have now shuttered and disappeared, some, like the Apollo Theater in New York City, Royal Peacock in Atlanta, Dreamland Ballroom in Little Rock and, yes, McCollum Hall, have survived to this day.

When white venues began to allow and even court Black entertainers in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the circuit’s viability waned. Thus, McCollum Hall was converted from a dance hall into a rooming house in the mid-‘80s before eventually falling into disrepair. It was finally acquired by the Fort Myers Community Redevelopment Agency, which has worked hard and assiduously to preserve and restore the building to its original condition and use. One step in this direction involved adding McCollum Hall to the National Register of Historic Places.

McCollum Hall is our very own brick-and-mortar homage to the art created by Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, Lionel Hampton, Otis Redding, Lucky Milliner, Duke Ellington and their peers decades ago. More expansively, it is a tribute to the resilience of African-American creative culture.

Count Basie

Though a pianist and occasional organist, William "Count" Basie's fame stems mainly from his history as one of America’s great bandleaders. Basie's arrangements made good use of soloists, allowing musicians such as Lester Young, Buck Clayton, Sweets Edison, and Frank Foster to create some of their best work. Although his strength was as a bandleader, Basie's sparse piano style often delighted audiences with its swinging simplicity.

Basie's mother taught him piano. Later, Fats Waller helped him find work in a theater accompanying silent films as an organist.

Beginning in 1927, Basie performed with two of Kansas City’s most famous bands in the city: Walter Page's Blue Devils and the Bennie Moten band. He started his own Kansas City band in 1935, engaging the core of the Moten band. They performed nightly radio broadcasts, which caught the attention of music producer John Hammond. Hammond brought the Basie band to New York in 1936. It opened at the Roseland Ballroom. By the following year, the band was a fixture on 52nd Street, in residence at the Famous Door.

“During this time, the key to Basie's band was what became known as the ‘All-American Rhythm Section’ –– Freddie Green on guitar, Walter Page on bass, and Jo Jones on drums,” notes the National Endowment for the Arts in its Freedom250 tribute to Basie. “The horns were also quite potent, including Lester Young, Earl Warren, and Herschel Evans on saxophones; Buck Clayton and Sweets Edison on trumpets; and Benny Morton and Dicky Wells on trombones. With a swinging rhythm section and topnotch soloists in the horn section, Basie's band became one of the most popular between 1937- 49, scoring such swing hits as 'One O'Clock Jump' and 'Jumpin' at the Woodside.' Lester Young's tenor saxophone playing during this period, in particular on such recordings as 'Lester Leaps In' and 'Taxi War Dance,' influenced jazz musicians for years to come. In addition, Basie's use of great singers such as Helen Humes and Jimmy Rushing enhanced his band's sound and popularity.”

Economics forced Basie to pare down to a septet in 1950, but by 1952 he had returned to his big band sound. In that year, he organized his "New Testament" band, which began a residency at Birdland in New York with such notable musicians as Frank Foster, Frank Wess, Eddie "Lockjaw" Smith, Thad Jones, and Joe Williams. Foster's composition "Shiny Stockings" and Williams' rendition of "Every Day" brought Basie a couple of much-needed hits in the mid-1950s.

“In addition to achieving success with his own singers, he also enjoyed acclaim for records backing such stars as Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Tony Bennett,” adds the NEW essay.

In 1958, Basie became the first African American to win a Grammy Award. He went on to win a total of nine Grammy Awards and by 2011, four of Basie’s recordings had been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Basie continued to perform and record until his death in 1984.

On May 23, 1985, William "Count" Basie was presented, posthumously, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan. On September 11, 1996, the U.S. Post Office issued a Count Basie 32 cents postage stamp. Basie is a part of the Big Band Leaders issue, which, is in turn, part of the Legends of American Music series. In 2019, Basie was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame.

Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington was a key figure of the Harlem Renaissance and not only one of the most important figures in the history of jazz, but in American music at large.

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington led his orchestra non-stop from 1924 to 1974. Over that span, his musical innovations and accomplishments were so numerous that they are difficult to comprehend, much less fully list. But his catalog or body of work drew much-deserved recognition. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (1960), a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1966), the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969 (the highest award a civilian can receive in the U.S.), an Honorary Ph. D. from the Berkley College of Music (1971),the Legion of Honor in 1973 (the highest award a civilian can receive in France) and, posthumously in 1999, a Pulitzer Prize “in recognition of his musical genius.”

The Duke defied categories. In fact, he steadfastly refused to conform to any preconception of what he or his music should be or do. Indeed, one of his greatest compliments was to describe an artist as “beyond category.” It is difficult to think of an artist who embodied that more fully and perfectly than Ellington did.

“As a composer, he wrote thousands of pieces, ranging from three-minute classics to hour-long suites,” writes Scott Yanow for Jazzfuel (January 12, 2023). “Scores of his originals became jazz standards, and he ranked with the other masters of the Great American Songbook such as George Gershwin, Cole Porter, and Irving Berlin. But unlike those composers, Ellington wrote his works not by sitting at home by a piano but while traveling on the road with his orchestra.”

As an arranger, Ellington mixed together virtuosos with primitive players, and repeatedly rearranged the pieces in his repertoire to accommodate the musicians who joined his orchestra over the years.

“Ellington was among the very first to write music specifically for the players in his orchestra and in his own way,” Yanow writes. “Rather than breaking the rules of conventional arranging, he simply ignored them and created the music that best fit his ideas and the sounds of his sidemen.

Ellington was also a consummate pianist.

“[A]long with Mary Lou Williams, [Ellington] was virtually the only stride pianist of the 1920s who continually modernized his style while never losing sight of his roots,” Yanow observes. “He influenced such later giants as Thelonious Monk, Randy Weston, Abdullah Ibrahim and even Cecil Taylor among many others.”

Ellington wasn’t just mentioned in the company of Gershwin, Cole Porter, and Irving Berlin. He was in the same league as Haydn, Johann Strauss, Jr., Liszt, Verdi and Puccini. And besides Monk, Weston, Ibrahim and Taylor, he impacted the lives and work of such musical giants as Charles Mingus, Gerald Wilson, Clark Terry, Cecil Taylor and Quincy Jones, who have, in turn, created legacies of their own.

“I think all the musicians should get together one certain day,” Miles Davis once famously proclaimed, “and get down on their knees and thank Duke.”

An entire panel of the Buck’s Backyard Mural at McCollum Hall is devoted to Ellington.

The Jazz Trio

The Gulf Coast Jazz Collective is now in its sixth season.

The Collective opened its season with “A Tribute to Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong.”

Paul Gavin

Paul Gavin is a drummer, teacher, composer and arranger in Tampa. Since graduating from the University of South Florida in 2015, Gavin has made his living exclusively as a freelance musician. He maintains an active schedule playing music around Florida, teaching privately and in schools, and writing for school programs and his own original music.

Read the rest of his resume here.

“I brought him aboard specifically to develop the Jazz Collective,” Kurtz said. “Paul actually grew up in Fort Myers. I've known Paul since he was a 15-year-old kid. He started in middle school, believe it or not, playing the oboe. He was not a great oboe player, and someone introduced him to the drums, I believe, in high school and he found his perfect medium. He went off to Tampa for more education and has made that his home. But he's a brilliant educator, brilliant composer, amazing musician.”

Zach Bartholemew

Dr. Zach Bartholomew is an award-winning jazz pianist, composer, and music educator. He is currently based in Miami, where he maintains an active performance career as one of the most heavily sought-after pianists, accompanists, and sidemen in the area. In both 2016 and 2017, he placed as one of the top three finalists in the highly acclaimed Jacksonville Jazz Piano Competition and more recently has been featured as a performer, composer, and bandleader at various national and international jazz festivals, including the Jacksonville Jazz Festival, Monterey Jazz Festival, Jalisco Jazz Festival, and Festival Miami, among others. He and his band have been featured on radio broadcasts, concert series, and regionally promoted events at music venues all over Florida. He has performed with professional organizations such as the Sarasota Pops Orchestra and the Naples Philharmonic.

In addition to his active performance career, Bartholomew is a music professor at the University of Miami Frost School of Music, Broward College, and Tiffin University and has been featured as a presenter and performer at national and regional music conferences.

As a bandleader, Bartholomew has taken his band on multiple national tours, headlining at some of the top jazz venues in the country. He has performed as a sideman with artists such as Sean Jones, Victor Goines, Brian Lynch, Dafnis Prieto, Dave Holland, David Liebman, Ira Sullivan, Carmen Bradford, Byron Stripling, Dan Miller, Scotty Barnhart, Cyrille Aimee, John Beasley, Charles Calello, and Kevin Mahogany. He is currently involved in numerous musical projects as both a leader and a sideman. One current project is his Florida “Jazz Access Tour,” a grant-funded outreach program that aims to provide communities and schools in Florida with world-class public performances and educational programs.

Brandon Robertson

Brandon L. Robertson is an Emmy-nominated director and notable upright/electric bassist originally from Tampa.

In 2009, he graduated from Florida State University with a Bachelor of Arts in music with a focus on jazz studies. In the same year, Robertson became a member of the popular Florida-based jazz trio The Zach Bartholomew Trio. In 2012, the trio released its first album titled “Out of This Town.” It received notable reviews from jazz critics.

In 2015, Robertson performed at the world-famous Dizzy’s Coca Cola Club in New York City with the nationally recognized FSU Jazz Sextet joining members of the JALC Orchestra.

Aside from being an active musician, Robertson is also an advocate in jazz/music education. He has presented jazz clinics, workshops, master classes, and guest performances in schools K-12 throughout Florida and taught at the Florida State University summer jazz camps for middle school and high school students. In the spring of 2016, he earned his Master of Music in jazz performance at Florida State University. During this two-year period, he directed jazz ensembles, small jazz combos, taught various music-related courses at the university each semester, and performed with traveling national acts visiting the campus. He was also a faculty member of Abraham Baldwin Agriculture College School of Music in Tifton, Georgia, where he taught applied bass and helped assist with the jazz ensemble.

Read the rest of his resume here.

Support for WGCU’s arts & culture reporting comes from the Estate of Myra Janco Daniels, the Charles M. and Joan R. Taylor Foundation, and Naomi Bloom in loving memory of her husband, Ron Wallace.

Sponsored in part by the State of Florida through the Division of Arts and Culture.