In last week’s essay, News-Press storyteller Amy Bennett Williams recounted a recent axe injury incurred by her son, Nash, which has also inspired this week’s offering. Most any parent can tell you that the first time their child experiences a serious injury, the emotions attached to that moment leave a prominent footprint in one’s memory. That was certainly the case for Williams’ as she recalls in this week’s essay.

Childhood Injuries

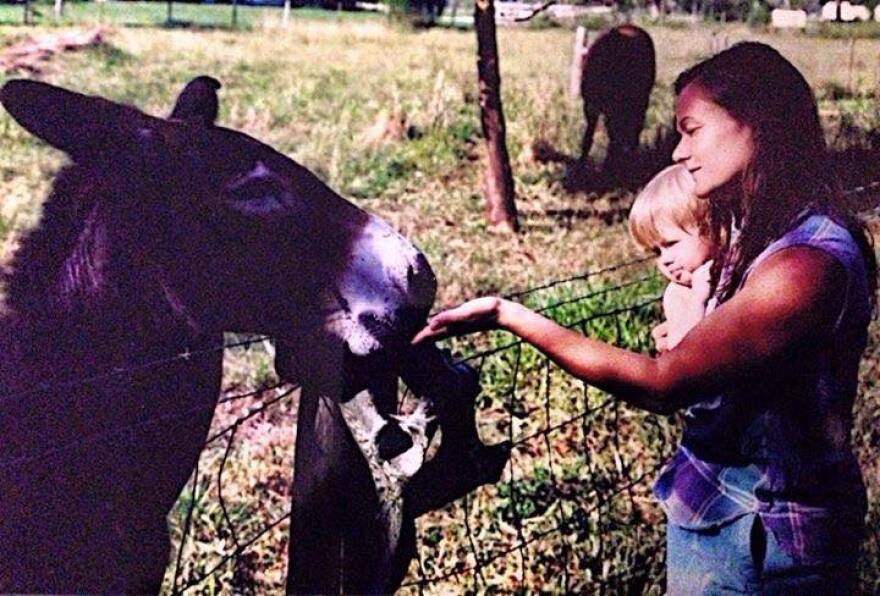

When my son, Nash, axed himself in the foot a while ago – a mishap mended with 17 tidy stitches - I recalled the first time I’d faced that sort of thing.

It was Easter and from my egg-peeling kitchen window vantage, I watched Nash come staggering from the woods, mussed and dusty, save fingerwidth rivulets streaking each cheek.

Though he was followed a moment later by cousins and an uncle, he seemed oblivious to them, alone, as he lurched toward the house.

He held his two arms in front of him, hands awkwardly clasped.

"Mama," he wailed, "I fell off the donkey."

Swooping in as one four-legged parent, Roger and I ushered our 5-year-old and his hovering entourage into the back bedroom to inspect his wounds. There were none to speak of, really, but then why the ragged sobs?

"My shoulder hurts. Really seriously,” he told us between whimpers.

He'd been riding our famously lazy donkey with his cousin Josie when it happened, he told us. Huh? Burrito usually does no more that lower his head, lock his knees and dig in when asked to walk. It turns out Nash's other cousin figured that if she held an apple in front of the donkey's nose, he'd move.

Did he ever.

Our good old placid lump of lower-order equine (for whom the word "mosey" was invented) had decided to chase the treat, walking right through a palmetto clump in the process, and scraping both kids to the ground.

They'd been riding double; they fell double -- Josie valiantly hanging onto her little cousin in hopes of breaking his fall. She got up scratched and scraped; Nash got up crying. You know the rest.

The Sunday night on-call pediatrician said we could wait until the next morning instead of hauling the boy to an ER (an experience we've come to despise) so we gave him some Motrin Jr. and pressed into service as a sling an old silk scarf that most recently had served as pirate gear. In the meantime, Nash was miserable. Sleep was pretty much out of the question, though we all managed to snatch a few minutes here and there.

The next day was a long slog from waiting room to waiting room: primary care doc to X-ray center to pediatric orthopedic specialist. The finding? A snapped clavicle, his pretty little bone broken clean through. Not much you can do about that, though, except keep it still.

So after setting out from home at 9:30 that morning, we returned nine hours later with only a blue Velcro sling to show for our troubles. That and the distinction (for Nash) of having the only donkey-related injury anyone -- from the radiologist to waiting room strangers -- had ever heard of.

After that, Nash got a little better every day, but not a whole lot. And I've had my nose rubbed in the fact that I'm abjectly feeble-hearted when my child's in pain.

I've been more than lucky, I'm aware. Nash's big brother, D.P., managed to make it through his first decade remarkably unscathed, except for a set of jumping-on-the-bed staples, so this is the first time I've had to witness one of my babies truly hurting.

Forgive me if you've been through this already. Forgive me especially if you've been through worse. But I can tell you, I'm not cut out for this.

When Nashie looked at me with a face full of pain, when he said, "Hold me, Mama," then reached, trembling, with just one arm, it all but undid me. Not that I've ever been one to indulge in hysterics, but I definitely felt the strain on the mooring tethers.

Of course, my inner Mr. T snapped, "Shut up, fool. He got off easy. You got off easy. Quit your snifflin.' "

I know that we live in a historical moment uniquely able to handle things like this (100 years ago here, the boy would have been on his own). I knew he was going to be fine. I knew six weeks is nothing. And I know you bring someone into the world at your mutual peril.

It helped that were are cooler heads around me.

"My best friend as a kid broke both his collarbones," my husband Roger told us. "Plus both wrists, both legs, both arms and his nose five times."

"Just the boy's first rodeoing accident," observed his honorary third grandfather, a Coloradoan and family friend who spent eight years as a rodeo cowboy.

My favorite came from Montana-raised Don Moore, the donkey's own doctor, who came (coincidentally) the next day for some routine maintenance on the equines.

When I told him what his patient had done to young Nash, he listened carefully.

"You know, there's a medical term for that sort of injury," he told me: "Childhood."